A Long-Awaited Transformational Leadership Strategy

The idea that a gender-balanced board of directors can positively impact the bottom line is well documented and becoming more widely accepted. According to a 2015 report from international audit and tax firm Grant Thornton, excluding women from board positions cost companies across India, the United Kingdom and the United States $655 billion (in terms of lower returns on assets) in 2014.

In its Women on Boards report published last November, MSCI ESG Research showed that companies with strong female leadership achieve a 10.1 percent return on equity, while those without attain only a 7.4 percent return on equity. Companies without strong female leadership also experience more governance-related controversies.

Increasingly there is meaningful debate around the world on how to get more women invited to the board table.

The United Kingdom offers one model for change—voluntary goals. The scarcity of women on boards became a hot-button issue for the nation in 2010. That year, women accounted for only 12.5 percent of Financial Times Stock Exchange (FTSE) 100 company board members. And while this number represented a 3 percentage-point increase from the 9.4 percent of women who made up boards in 2004, government and some corporate leaders felt the pace of change was nowhere near good enough. In fact, according to the U.K. Equality and Human Rights Commission, at that rate it would have taken more than 70 years to achieve gender-balanced boardrooms in the country.

In an effort to speed up progress, the government tasked Lord Mervyn Davies, former U.K. trade minister and past chairman of Standard Chartered bank, with bringing women into the boardroom. In 2011, Davies  published his first Women on Boards report, which laid out a clear directive for the nation’s FTSE 100 executives: Voluntarily increase female representation on boards to 25 percent by 2015 or, although not recommended by Davies, possibly face government-directed mandates for change.

published his first Women on Boards report, which laid out a clear directive for the nation’s FTSE 100 executives: Voluntarily increase female representation on boards to 25 percent by 2015 or, although not recommended by Davies, possibly face government-directed mandates for change.

“You can’t carry on with a board that does not represent your employees or customer base,” Davies told The Telegraph in 2012. “If we don’t have equality in business between men and women, we’re just not going to be competitive internationally.”

“You can’t carry on with a board that does not represent your employees or customer base. If we don’t have equality in business between men and women, we’re just not going to be competitive internationally.”

—Lord Mervyn Davies

Despite initial backlash and continued skepticism from some executives and experts, in October 2015 Davies announced that not only had the 25 percent voluntary goal been met, it had been exceeded. According to the latest annual Women on Boards report, now better known as the Davies Review, in 2015 26.1 percent of board members of FTSE 100 companies were women.

Further illustrating the United Kingdom’s success is the fact that for the first time ever, there are no all-male boards in the FTSE 100, Share on X according to the Davies Review. In fact, only 15 male-only boards remain among the FTSE 250—a dramatic decrease from the 131 that existed when the report began.

Despite the strides by U.K. companies, Davies isn’t declaring “mission accomplished.” He is now championing a new target for U.K. companies: Increase the percentage of board seats held by women to 33 percent by 2020. (This new goal would still put the United Kingdom behind Norway’s world-leading female board member percentage of 35.5 percent.) He has also widened the challenge to include all FTSE 350 firms.Companies on the Fortune 500 list can’t make such claims. According to the latest data available, 23 Fortune 500 companies still have all-male boards. Ten Fortune 250 companies have zero female board members—four of which are also on the Fortune 100 list.

Mandating Progress

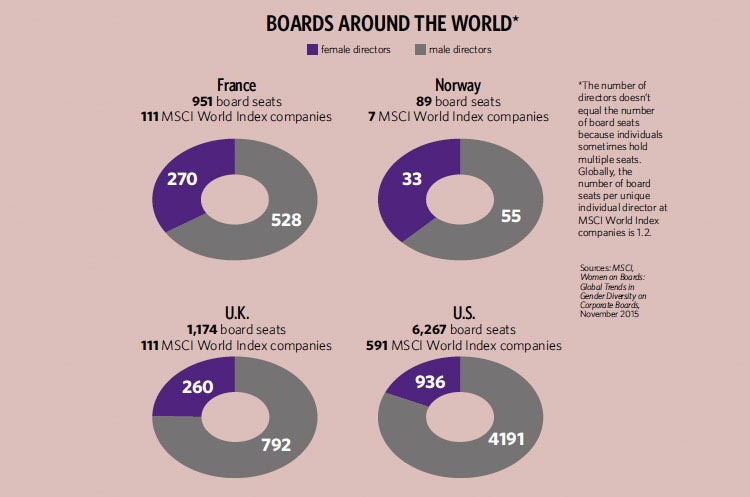

Progress in the United Kingdom not-withstanding, increases in female board representation globally are “glacial,” according to MSCI. Women hold 18.1 percent of directorships worldwide; they held 15.9 percent in late 2014. Emerging markets, where only 8.4 percent of board members are women, drag the number down.

In an effort to keep their economies from falling behind, 10 countries—including Belgium, Italy, France, Malaysia and United Arab Emirates—mandate some form of board gender diversity, according to MSCI, while another 14 have established requirements for state-owned enterprises.

These mandates do not always mean easy or swift compliance. For example, in 2014, India’s Securities and Exchange Board issued an ultimatum to publicly traded companies: Add at least one female board member or face repercussions. More than 500 companies listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange and 200 on the National Stock Exchange missed the April 2015 deadline and faced fines until an appointment was made, according to Reuters.

The companies that did comply are not all worth celebrating, however. According to PRIME Database, more than 700 of the companies appointed directors who cannot be considered independent because they are either family members or have another vested interest.

“Companies [in India] need to be more serious about the whole idea of having women directors, which is to promote diversity. Having a woman from the promoter group or family defeats the purpose,” Pranav Haldea, managing director of PRIME Database, told Catch News.

“Compliance is being done only on paper,” he told CNN Money.

Despite some pushback, some governments and government agencies are not shying away from promoting gender diversity. According to MSCI, several countries, including Canada, South Africa and Korea, all have possible quotas pending.

And in January, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Chair Mary Jo White announced her agency would be reviewing existing company disclosures to provide recommendations on whether a change is needed on how much detail companies provide about the racial and gender makeup of their boards. This announcement follows a U.S. Government Accountability Office report released just weeks earlier, which quoted a public fund fiduciaries petition when it said that some companies have so much leeway in how they define diversity that “the concept conveys little meaning to investors.”

“Board diversity is an indication that a company is progressive and future-oriented. A company with a progressive culture from the top down through the ranks will perform better.”

—Reatha Clark King, chairman of the board of the National Association of Corporate Directors

How Much and By When?

Government leaders aren’t the only ones issuing calls for equal representation on boards. Corporations, associations and non-profits are also leading the charge for change.

“Companies realize that diversity is a business imperative; more specifically, a talent imperative,” says Reatha Clark King, chairman of the board of the National Association of Corporate Directors and a member or former member of seven corporate boards. Many companies also see diversity—including cultural and gender diversity—as an asset for addressing ever-increasing complexity in the global marketplace, she says. Some companies even note in their proxy statement that the ability to deal with complexity is an expected competence—collectively and individually, according to King.

Despite the research, many women board members are reluctant to draw causality between board makeup and a company’s financial performance. Instead, they emphasize what it means for an organization’s leadership strategy.

“You have to be very cautious about the chicken and egg,” says Kim Van Der Zon, who leads board search for the global executive search firm Egon Zehnder International. “It’s very difficult to say that just because a board has three or more women it will perform better.” If that were the case, every corporation would simply add a third woman to the board and wait for the inevitable results. “It’s more about the mindset of the overall board and the company itself that makes them more financially successful, which means that they are more inclined to see diversity in the boardroom as a positive.”

King agrees. “Board diversity is an indication that a company is progressive and future-oriented,” she says. “A company with a progressive culture from the top down through the ranks will perform better.”

Absent a government mandate, King believes a voluntary initiative for board diversity is the only way to make it happen. In 2012, the U.S. Committee for Economic Development (CED), a nonprofit, nonpartisan, business-led public policy organization that delivers analysis to influence solutions to critical issues that impact the health of the U.S. economy, released the policy statement Fulfilling the Promise: How More Women on Corporate Boards Would Make America and American Companies More Competitive.

In this report—which examines the current state of corporate boards and urges companies to make it a priority to develop the talents of female staff who have been identified as potential leaders—the CED position advocates major corporations adopting a policy of recruiting women in one of every two board seat openings.

At the same time, the CED recommends meeting with board nominating committees to explain the importance of hiring female members and expanding their criteria for candidates to break down the typical barriers to entry females may face. This includes looking beyond the typical list of current and former CEOs and considering senior female executives with a strong business background.

A variety of organizations and global executive search firms have also signed on to MSCI’s “Inching to 30 percent” global goal, a target that, at current rates, will not be reached until 2027.

For Van Der Zon, that goal is still too low.

“Shouldn’t it be 50 percent?” she asks. “Shouldn’t it represent the market at large? That scares people off, but I do think that wishing that and helping companies move toward that should be our goal. It’s not just in the boardroom. It’s throughout the executive ranks because that’s where the pool of board members comes from.”