Stoking the Fires of Transformation

As a young ensign and naval aviator, landing on the ship was a source of great stress tension, and lots of sweat. I tried every tip and technique to relax and make it easier — to change the situation, but it never really improved.

One day, I was flying with a mustang lieutenant commander, returning from a mission. “Okay, Nate, you’ve got it. Bring us in.”

I locked my eyes on the deck of the carrier — pitching, slewing, and rolling — and could feel my grip on the stick tighten automatically; sweat began rolling down my spine. Starting down the glide path, I tried to keep up with the dancing motion of the ship.

Jack Shioli’s voice came through my earphones, “Look at the horizon.”

Every instructor with whom I had ever flown said, “Look at the horizon.” I glanced up at the horizon to comply and immediately bore-sighted right back to the deck of the ship.

“Dammit, Nate, look at the horizon.” Jack grabbed my helmet and pulled my head up, so that I had to actually see the horizon. I realized that, while the ship was moving all over the place, the horizon was not moving. A moment later, we eased on the deck.

After that I never had a problem landing on the ship — a transformation in my experience and ability, not just a change.

Change and transformation are not the same. Having said that, if you read most management literature, visit the websites of the big IT consulting firms, and listen to corporate executives, you would conclude that transformation is simply big change. This lack of distinction is costing companies and other organizations significant opportunities for real competitive advantage and organizational success. Different than what? Different than what already is? Different than the past? Change, by its very nature, is rooted in more than, different than, or better than what has been. Change keeps us attached to the past in some way.

Apple’s dictionary defines change as “make or become different.”

The same dictionary defines transformation as “(in physics) the induced or spontaneous change of one element into another by a nuclear process.” Think transubstantiation.

Transformation is putting the past where it belongs, in the past, and not letting it determine the present or the future.

Looking at change in mathematical terms, you start with X, which represents current circumstances, and then you change x or ΔX. You end up with some function of X or ƒ(X). That is change.

With transformation, you start with current circumstances, represented by X and then, putting X into the past, you have ø and end up with {…} — a space of possibility within which you can create possibilities, a new something or, even, some of X that is desirable. This is transformation. This work is absolutely essential before an organization can transform. By completing the past, you generate a space to create — not fix or improve or upgrade. It is this space of creating from nothing that distinguishes transformation from change. Without doing this work, the best you can expect is good change.

Transformation is a powerful discipline for shifting what people think is possible in a company and what is possible for themselves. At its most fundamental level, transformation is opening up a new possibility or a shift in one’s point of view.

In the ’70s, Werner Erhard, who Fortune called the father of humanistic management, developed a method of personal transformation with the highly popular “est” training. In this training, people from all walks of life created new possibilities for themselves and transformed their lives. A decade later, these generating principles began to be widely applied in businesses and other organizations and institutions.

As far as we know, the first intentional organizational transformation of a large corporation occurred at Ford Motor Company. In the midst of the onslaught of Japanese competition, Don Peterson and Harold “Red” Poling, Ford’s CEO and COO, realized that Henry Ford’s corporate culture was no longer a source of the company’s success and was actually interfering with the company’s ability to compete in a rapidly globalizing marketplace. They wanted to replace the old culture, not merely change it. Nobody knew how to do it but doing so was an organizational imperative.

When we began working with the automaker in the early ’80s, we interviewed executives, managers, and line employees. At Ford, they talked about “The Job” and “Job One” as a shorthand for an urgent priority. We asked a plant manager what Ford’s number-one job was; he replied, “Getting cars out,” the answer that we heard most often in one form or another. When Red Poling was asked the same question, he replied emphatically, “Quality is job one.” That one statement, the COO’s crystal-clear stand, was transformative. The now famous ad slogan “At Ford, Quality Is Job One” encapsulated the transformation that fueled the company’s sluggish sales and degrading reputation, leading to record profits.

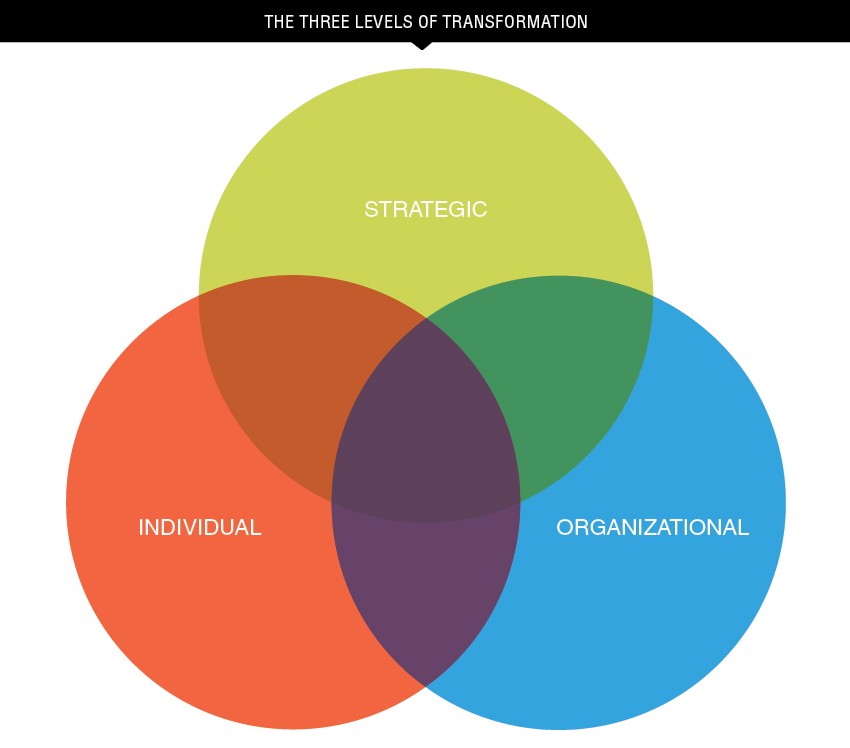

Transformation occurs on three levels: individual, organizational, and strategic. Sometimes, a transformation in strategy requires an organizational transformation and then the people in the company have their own personal transformation. Sometimes, an organizational transformation opens up a strategic transformation. Most often, a CEO sees new possibilities for the company and leads the organization’s transformation.

How does a leader inspire, lead, and realize transformation in her or his organization? Quite simply, by being transformed him or herself.

Warren Bennis, who just passed away and who was the godfather of leadership studies, points to a crucible experience as a common thread that he discovered in hundreds of transformed business leaders. He defines a crucible experience as a severe test or trial that is intense, often traumatic, always unplanned, and transformative. “Crucibles,” explained Bennis and his co-author, “force leaders into deep self-reflection, where they examine their values, question their assumptions, and hone their judgment.”1 As a transformed individual, he or she is not managing the organization based on the past; his or her leadership is based on their commitment to a new future for the organization that is discontinuous from its past.

As Tim Bailey, Executive Vice President, Global Product Supply, Business Services & Technology, at S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc. puts it, “If you start with possibility and work your way back to the current circumstances, you always end up with something bigger than if you start with the circumstances and try to figure out what is possible.” Tim is a brilliant, transformational leader who knows what it takes to cause a breakthrough, having led and championed dozens of breakthrough projects that have brought hundreds of thousands of dollars to the bottom line.

In the Winter 2013 issue of IQ, Werner H. Erhard and Michael C. Jensen authored “The Four Ways of Being That Create the Foundation for Great Leadership, A Great Organization & A Great Personal Life.”

These foundations are central to a leader’s transformation and ultimate success in transforming his or her organization.

How does an executive know that it is time to transform the organization? The most common sign is that by doing what it knows to do with a reasonable rate of improvement, the likely results are not acceptable or satisfactory. Amazingly, the best time to transform is on the shoulder of organizational success — just when everyone else wants to reproduce and proceduralize the source of that success.

Most companies are saddled with “that’s the way we get things done around here” or “that’s the way things work around here.” We call that ‘business as usual’ which sets up predictable results that we call ‘the drift.’ These are proven ways of working and operating that reduce risk and deliver expected results. Performance improvement is tied to past performance. The best that can be achieved is incremental improvement.

Breakthrough performance requires a transformation — breaking out of the business as usual — inventing anew the way the organization perceives what is possible and thinks and acts. Transform any one element — perceiving, thinking, acting — and you are on the road to transformation and breakthrough performance.

1. Bennis, Warren G. and Thomas, Robert J., “Crucibles of Leadership,” Harvard Business Review, September 2002, pg 1.

Authors Werner H. Erhard and Michael C. Jensen describe the four foundations of being a great leader as such:

- Being authentic

- Being the cause in the matter of everything in your life

- Being committed to something bigger than yourself

- Being a person and an organization of integrity

A plant manager at a large telecommunications firm told us, “All of this quality stuff is just a waste of time. But, I’m going back to the plant and acting like I believe in it because that is what the company wants.” At the time, Total Quality Management was relatively new and was transformational when done right. He started acting in the way that his manager expected him to and simply repeating what he heard in our work session. Four months later, he was the company’s biggest proponent of total quality next to the chief quality officer and the CEO. He saw the impact of his new actions on his people and the results that they were producing. This transformation in acting led to a transformation in thinking and perception that began the transformation of his plant and achieving a breakthrough in performance: a 32 percent increase in quality and a 27 percent decrease in cost in two years.

Transformation happens in a moment and, at the same time, is a structured journey. The first step is facing reality, separating fact from interpretation and assessment and peeling back the long-held layers of belief and misperception that are inherent in the corporate culture. As a part of this work, we interview and survey a big sample of folks from every level and every function. We listen for aspirations as well as likely barriers. We ask, “When you need advice about something, to whom do you go?” and “When you hear a rumor, with whom do you check it?” The folks whose names are mentioned most often are invited to serve with selected executives to lead the effort.

Next comes letting go of decisions about how it is and must be and putting those in the past, creating a space to design a future from possibility. This also requires confronting the future that is predictable based on business as usual and the drift.

Starting with this blank sheet of paper, the executives work together to create a bold, exciting, inspiring, and challenging future for the company. We use the Merlin process, working backwards from the future to the present, to identify what it will take to make the future happen and to get the organization to achieve a breakthrough. The executives then design a corporate culture that will pull for success in that future, one that would be a source of competitive advantage in the marketplace of the future.

Then, we launch an intensive campaign to enroll everyone in the organization. Both titled and informal leaders enroll people throughout the organization to inspire and gain authentic commitment.

When people are truly enrolled — having authentically chosen to get on the bus traveling the transformation journey — sustaining transformational momentum is relatively easy, given executive courage and sustained commitment. There is nothing more transformative than involving people in the work to achieve transformation, so we get people to work on projects that are critical to fulfilling the new future.

The projects are derived from a keystone project that was designed and committed to by the executives. A keystone project is a commitment to critical business results that are achievable only in the new culture. The keystone project team is led by the CEO and made up by select executives and key informal leaders.

The first ground rule for the project teams is to operate consistent with the new culture. A cross-functional team works on the project, and, as they progress, the process of transformation is accelerated. This focus on performing work and achieving results that seemed impossible in the old culture keeps everyone’s eye on the prize.

Managers are equipped to educate employees about the changes that are taking place, what’s different, what the organization won’t be doing any longer, and what the company will start doing differently. Every person in the company is educated in how to operate in the new culture and is given the opportunity to discover what aspect of the new future inspires her or him. They have the opportunity to sign up for various roles in the company’s transformation: project team leaders, project team members, coaches, and trainers. The executive team serves as the steering committee for transformation with the CEO leading the entire effort.

Paradoxically, the biggest barrier to transformation is past success. We all want to win. Once we have a formula for winning, we hold on for dear life. When the formula for success stops working, we tend to hold on even harder, do more of what made us successful. This is true for executives and organizations. They are like a survivor in the middle of the ocean holding onto a deflated life preserver. As long as they hold onto the past, even past successes, transformation is not possible. The point is not to forget the past; the point is not to be dictated to by the past.

The second key barrier is senior executives’ need to look good and be well thought of. Most senior executives operate like they know more than anyone else in the room. The bad ones operate like they are the smartest ones in the room. It is a rare executive who openly admits mistakes and is willing to be accountable for failures. The myopia produced by success and looking and sounding like you know it all precludes transformation. Too many executives are unwilling to let go of what has made them individually successful for the possibility of greater organizational success. Putting the past in the past and venturing into the unknown territory of a new, unproven possibility involves a high risk of failure. In a transformed organization, everyone is a beginner. Better to keep doing what you are already doing to look good and appear smart.

The third barrier is closely related to the second: fear. Fear of failure. Fear of the unknown. Fear of looking bad. Fear of loss of approval. Fear of not being liked or not fitting in. There are almost no facts known about the future. Indeed, the nature of the future is that it is unknowable. What can be predicted is a kind of security blanket for too many executives. Predictability has given them confidence that they will succeed. Fear freezes them, stops radical thinking and acting which in turn stifles the possibility of transformation. In the middle of every transformation effort on which Insigniam has worked, there is a moment of truth — the valley of the shadow of death — in which the transformation becomes risky and the executives want to go back to what they know. If they do, this ends transformation, and the people who are the organization are demoralized. When the executives lead and choose to persist — despite contrary evidence — breakthrough results start to build up.

If you can see opportunities that are outside the reach of your organization, embrace transformation. Put the past in the past. Create a space for possibility. Enroll others in the transformation. These are the ingredients for stamping out the instrumentalism of change and stoking the fires of transformation.