Beyond Sustainability: A Paradigm Shift Is Overdue

In 1972, the Club of Rome published a report that sounded an alarm for corporations, institutions and governments worldwide. The Limits to Growth (also known as The Meadows Report after two of its authors) raised the issue of businesses’ impact on the environment and introduced the consideration of this impact into corporate strategic choices and day-to-day operations.

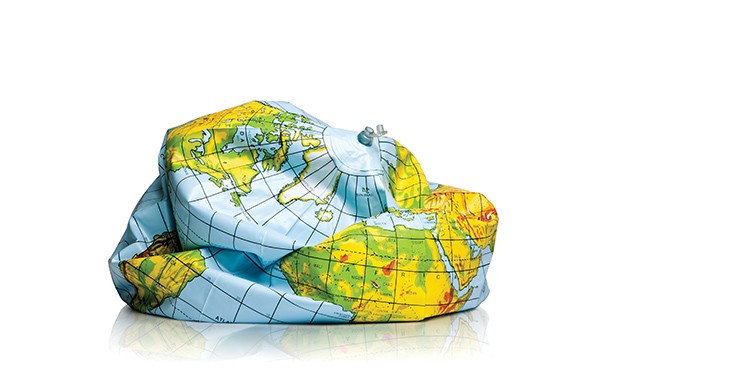

The report shed light on the danger of exponential economic and population growth in a world with finite resources. Its conclusion was startlingly blunt but clear: The planet’s ecosystem simply could not sustain the trajectory of economic growth that we as businesses traditionally seek. Should historical growth trends continue, the result would be a “sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity.”

The concept of sustainable development was made well known in 1987 by Norway Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland. In a widely received report, Ms. Brundtland described it as a development that “meets the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs.”

Known as the “Mother of Sustainability,” Ms. Brundtland was instrumental in making sustainable development an international topic with a landmark report known as Our Common Future, backed by the World Commission on Environment and Development. The document introduced a robust conceptual framework of sustainability involving three critical areas and their interdependence: environmental protection, economic improvement and social equity.

Given these early calls to radically shift our economy, it is difficult to realize that nearly 50 years after The Limits to Growth sounded the alarm, we face the same urgent demands for change. Sustainable development has failed. Development is surging, but sustainability is seriously compromised.

The Limits of Sustainable Development

Since 1987, the concept of sustainable development, as embraced by businesses and organizations, has been refined to address the issue through the three main approaches outlined in Our Common Future: the environmental, financial and social responsibility of organizations.

Most decisions and initiatives are driven by the goal of decreasing negative impact: turning a significant negative impact into a lesser negative impact. The problem with these initiatives lies in their very intent; they still produce an impact, operating within the paradigm that our business and human activities cannot avoid harming the environment.

The deterioration of our environment today demonstrates we are not even close to intervening in the decline of our planet and its resources. This is because the concept of sustainable development operates in a failing paradigm. Development as we understand it cannot be sustainable. If we want fossil fuel–powered cars, we will inevitably bear more environmental incidents like the Deepwater Horizon disaster in 2010, the largest ever accidental marine oil spill. If we go for a “cleaner” option and choose an electric Tesla, countless children will be exploited in the Kivu region of the Democratic Republic of Congo as they mine for cobalt—a critical metal used in electric car batteries. We deceive ourselves by pretending traditional development is possible. We have forgotten that this model of development relies on the neglect and misuse of a living and limited physical environment.

Toward the Restoration of Ecosystems

Our business community has made great progress toward greening its operations. Efforts include cutting the emission of CO2 and other harmful chemicals; reducing the use of water and increasing availability of safe water; and less reliance on fossil fuels, which is based on a shift to renewable sources of energy, fair-trade schemes and more.

Trending in the Wrong Direction

As The Limits to Growth made clear, if growth trends are allowed to continue, the planet will face a “sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity” by 2072. What would this decline look like? The report provides specific examples. Its predictions include:

- Global industrial output per capita peaking by 2008, followed by a rapid decline

- Global food per capita peaking around 2020, followed by a rapid decline

- Global population peaking in 2030, followed by a rapid decline

These actions reflect the current efforts of sustainable development that focus on reducing the negative impact and the cleanup of environmental messes. But it will not be enough. Irreversible damage has been done. If we are truly interested in a sustainable economy, changes have to occur: Our operations must focus on the restoration of the eco-systems within which the economy works. Share on X

A major conclusion of The Limits to Growth is that the unsustainable growth trends first recognized in 1972 could be altered, and therefore sustainable ecological and economic stability could be realized. Humans can no longer live at the top of their ecosystem and extract resources that release the waste products of their activities.

People live within their ecosystem. The challenge now is to protect it so not only can the last two centuries of damage be erased, but our ecosystems can be replenished to anticipate the planet’s growing human numbers. It is not a question of saving the planet but also of saving ourselves. The planet will not disappear, but we might, and other species will also be casualties.

The absolute measure of an ecosystem’s health is the level of biodiversity and the ability to increase its biomass. The opportunity is for business activities to be reoriented not only to prevent disruption of this goal but to actively enable its realization. Critical to this paradigm is the recognition that our economy operates within an ecosystem, according to German scientist Ernst Haeckel’s definition of ecology:

“By ecology we mean the body of knowledge concerning the economy of nature—the investigation of the total relations of the animal both to the inorganic and to its organic environment; including, above all, its friendly and inimical relations with those animals and plants with which it comes directly or indirectly into contact.”

A comprehensive understanding of this ecosystem includes the environment as well as all of its living inhabitants. A modern way to understand ecology involves the science and study of the interdependencies that condition our ability to survive.

For four decades, Insigniam has supported companies as they transform their operating paradigms. One truth we have discovered: Any operational transformation in an enterprise is possible when there is a committed coalition of leaders. The same can be said for a social or industrial transformation. Anything can be achieved if people with different concerns come together with a common commitment. If, as companies, we want to transfer an economic playing field to future generations, our call is to collectively set goals that support biodiversity restoration and biomass increase everywhere our companies operate—directly and indirectly. This is a reinvention of the game.

“If, as companies, we want to transfer an economic playing field to future generations, our call is to collectively set goals that support biodiversity restoration and biomass increase everywhere our companies operate—directly and indirectly.”

Reimagining How Businesses Operate

The severity of the threats to our ecosystem has been known since the publication of The Limits to Growth. Looking past political debates about whose responsibility it is, the challenge is to examine who has the capacity to respond to the urgent demand for a transformation in how this crisis is approached. The opportunity lies with businesses, and us as business leaders.

We talk a lot in business communities about how technology has transformed the economy and the workforce. Businesses face constant disruption from technology and the need to digitize our operations. Communities—local, state and federal—are grappling with the economic consequences of replacing manual jobs that sustained generations of families. Businesses, governments, think tanks and communities are struggling to discover how we can reap the benefits of technology while transforming the skills of our workforces.

The good news is that there is an opportunity not only to recover our environment but to build a thriving and humane economy that works for everyone. Concerns for our climate typically focus on biological consequences such as the death of coral reefs, the decimation of rainforests and the size of one’s carbon footprint. However, a less-discussed consequence is the impact of environmental degradation on human communities. This involves children growing up in homes that have polluted drinking water. This involves entire generations suffering from cancer and other diseases triggered by their proximity to toxin–spewing industrial activity. This involves families wrecked by the economic precarity caused by a threatened dependence on natural resources.

The push toward sustainability offers a key opportunity for C-suite executives. What could this look like? An example: the harvesting of all raw materials might involve not only the extraction of resources but also the concurrent restoration and building of new ecosystems. This would balance the impact of the reduced biodiversity caused by a monocultural field. For example, an acre of harvested soy is compensated by x square meters of planted hedges.

Another way that our business community can reimagine sustainable development is to invest in low-tech solutions that can be developed with renewable energy and materials, or through repurposing waste. An example is solar heating systems made of recycled Plexiglas rather than the traditional shiny, high-tech solar panels. This activity both reduces waste and serves the purpose of providing energy. These examples demonstrate the vast range of possibilities that arise when businesses embrace a strategic focus on this reimagined paradigm of sustainability.

But the potential goes far beyond environmental benefits. It also offers a solution to the need for stable career tracks for people whose jobs were displaced by technology. The activities discussed here can offer a solution to the absence of low-skill, industrial labor jobs. As business leaders, we can collectively commit to building a future job market that includes accessible, inclusive employment at livable wages while simultaneously meeting the ecological goals of our community. Doing so allows us to address two challenges at once: restoring our biological ecosystem and transforming our economic ecosystem. This paradigm shift represents an opportunity for our global community that simply cannot be missed. Why don’t we seize it?

This article appeared in the Winter 2021 issue of Insigniam Quarterly. To begin receiving IQ, go here.