Burnout is Breaking Your Board

When Jeffrey Sonnenfeld talks about executive burnout, he doesn’t frame it as a matter of self-help or stress management. He doesn’t speak of yoga retreats, meditation apps, or resilience coaching. Instead, he goes straight to governance. Burnout, he insists, is not a private affliction or an HR box to be checked. It is a systemic risk that eats away at decision-making, strategic clarity, and long-term value creation. If left unchecked, it is as damaging to an enterprise as a cyberattack, a supply chain collapse, or a regulatory failure.

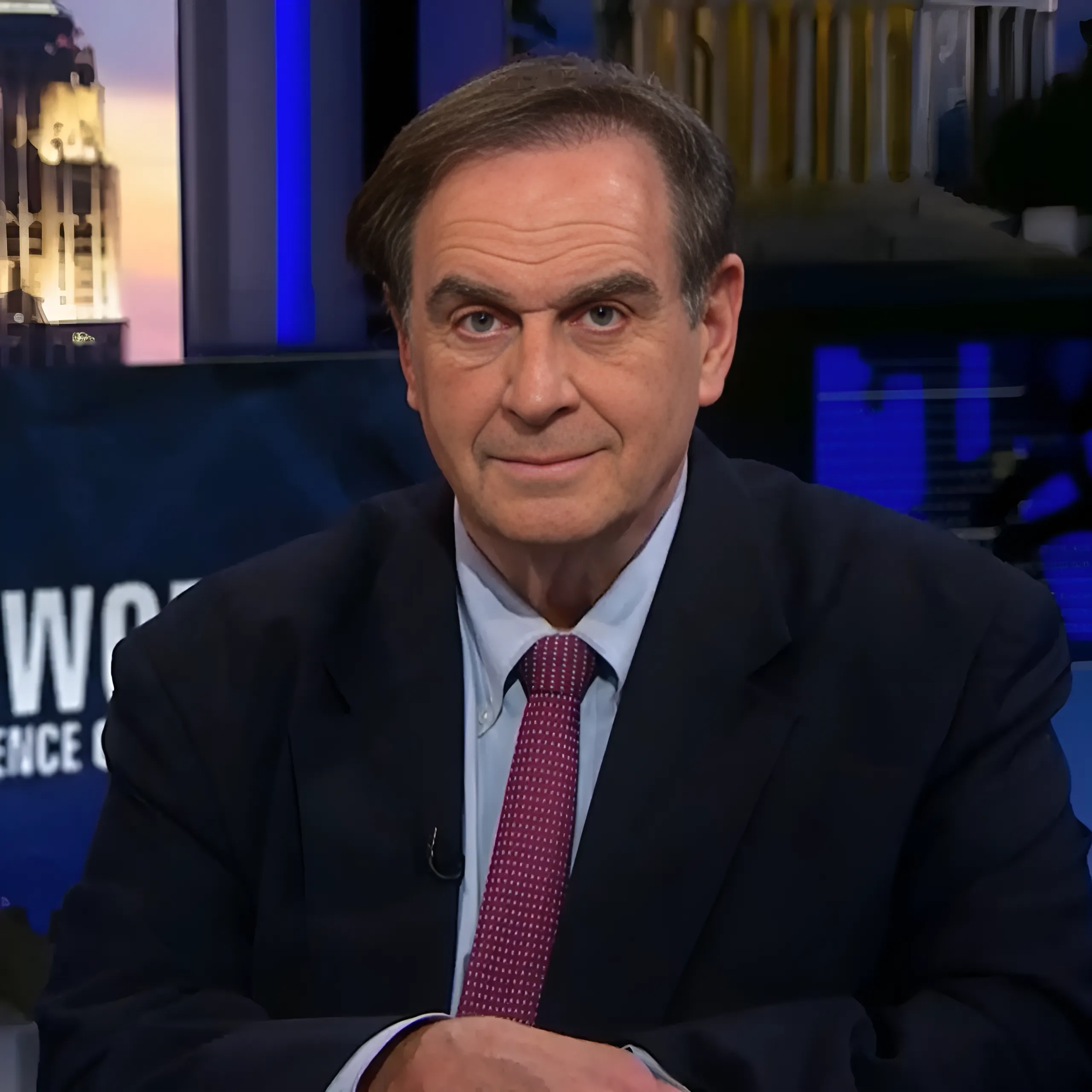

“Executive burnout has become a major challenge not only for management teams but for boards themselves,” Mr. Sonnenfeld says. “It’s not just about individual resilience—it’s about how the board runs, how meetings are conducted, and whether the culture enables or exhausts leaders.”

It is a striking reframing from one of the most authoritative voices in corporate governance. As Senior Associate Dean for Leadership Studies at Yale School of Management and founder of the Chief Executive Leadership Institute (CELI), Mr. Sonnenfeld has advised thousands of CEOs and directors, witnessed boards stumble and recover, and seen how fragile leadership capacity can become under relentless disruption.

Cited as one of the 100 most influential figures in corporate governance, Mr. Sonnenfeld has been recognized by BusinessWeek as one of the world’s 10 most influential business school professors and by Worth magazine as one of its “Worthy 100 Leaders.” Frequently cited by The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Economist, and The Financial Times, he has advised the White House, the U.S. State Department and Treasury, and the Council of Economic Advisers. His CELI summits draw a who’s who of global leadership—from Jamie Dimon, Bob Iger, and Satya Nadella to Janet Yellen, Larry Page, and Volodymyr Zelenskyy—to tackle the most urgent challenges of our time. For him, burnout is not a matter of personality; it is a matter of design.

When the Board Becomes the Problem

The conventional wisdom holds that directors protect executives from overreach, anchoring them in strategic oversight and long-term vision. But as Mr. Sonnenfeld tells it, boards themselves often create the conditions that drive leaders toward exhaustion. He points first to the tyranny of the slide deck.

“Too many board meetings are consumed by encyclopedic PowerPoint presentations,” he explains. “They go on for so long that they consume the oxygen in the room. Board members sit there passively, numbed, unable to engage because they’re wading through a performance rather than participating in a conversation. And when management insists on holding back materials until the meeting, it only compounds the problem. Instead of preparing, directors are caught flat-footed, as if the goal were a big reveal. That’s not governance—that’s theater.”

The remedy, he says, is simple but rare: distribute materials well in advance, encourage directors to prepare on their own, and reserve meeting time for genuine dialogue.

“If you’re going to bring people together, make it conversational, make it interactive. Let them connect dots, challenge assumptions, and push the thinking further. Otherwise, you’re wasting talent and accelerating exhaustion.”

What makes this diagnosis particularly sharp is that it addresses burnout at the structural level. Executives already juggle relentless demands, crises, and shifting expectations. When board meetings add tedium and inefficiency to that mix, they don’t just waste time, they drain capacity that leaders desperately need for strategic clarity.

The Tyranny of Tradition

Mr. Sonnenfeld is equally unsparing when it comes to the traditions and rituals that have calcified in many boardrooms. Over the years, governance reformers have pushed for independence, objectivity, and checks against cronyism. But in the process, they created new orthodoxies that often leave boards less effective and executives more isolated.

“One of the pathologies that developed from the governance movement was the idea that only the CEO should be on the board from management,” Mr. Sonnenfeld says. “There’s no evidence that excluding other senior executives makes boards stronger. In fact, it deprives directors of hearing directly from the people closest to the issues. Not because CEOs are dishonest, but sometimes they’re not the most eloquent, or they unintentionally underplay something. When you have other executives in the room, the conversation is richer, and the board has a fuller understanding.”

The same critique applies to outdated rituals of deference. Mr. Sonnenfeld recounts how a major beverage company once told new directors not to speak for their first year, a practice that Jack Welch—never one to hold his tongue—immediately rejected. He tells of banks with boards so large they resemble classrooms, with members seated in neat rows, unable to spark real dialogue.

At one major U.S. bank, he recalls, the board’s size and seating killed conversation—until he suggested rearranging the chairs into a semicircle. The discussion transformed instantly.

“It sounds trivial,” he says, “but the physical layout of a room can determine whether you get a lively crossfire of ideas or a scripted routine. Too often, boards fall into rituals that are more about habit than effectiveness. And when meetings become ritualistic, people disengage. That disengagement is the soil in which burnout grows.”

Burnout, he says, is not only about workload; it is about wasted work. Executives feel fatigue not just because they are busy, but because they are busy in ways that don’t add value. A board that clings to rituals for the sake of tradition only amplifies that waste.

Reading the Warning Signs

The warning signs of leadership fatigue are not always obvious. Declining results or missed targets might eventually reveal the toll of burnout, but by then, the damage is already done. Mr. Sonnenfeld urges boards to watch for subtler signals that executives are losing focus or capacity.

“There are five or six things to look for,” he explains. “Sometimes you’ll see directors or executives asking questions that have already been thoroughly answered—that’s a sign they’re not paying attention. Other times, they’ll ask something so basic that it was covered in the preparatory material, which tells you they didn’t do the homework. Another red flag is when you notice confusion that nobody dares to voice during the meeting. You hear it later in the hallways, whispered among colleagues. That means the culture of the boardroom isn’t safe enough for candor.”

Other telltale signs include irritability, short tempers, and emotional reactivity—executives snapping at questions or losing patience more quickly than usual. And then there are the directors who fixate on logistics—when the break will be, what’s for dinner—rather than substance. All of these, Mr. Sonnenfeld says, are symptoms that the system itself is under strain.

“Burnout doesn’t always look like collapse,” he says. “Sometimes it looks like repetition, distraction, or obsession with process. Boards need to be alert to these cues, because they tell you the leadership capacity of the organization is being eroded.”

Breaking the Silence

If boards are to play a constructive role, they must be willing to look in the mirror. That means asking hard questions about whether their own dynamics are contributing to the problem. Mr. Sonnenfeld recalls how Jack Welch once forbade directors at GE from speaking to each other outside formal meetings, a practice he considers disastrous.

“A board that can’t talk to itself is a board that can’t govern,” he insists. “Directors should feel comfortable comparing notes, asking questions, even bringing in outside experts to validate what they’re hearing. When management tries to prevent that, it’s a troubling sign. It creates suspicion and isolates directors from each other. That isolation doesn’t protect against burnout; it accelerates it.”

For Mr. Sonnenfeld, healthy boards create a culture where candid dialogue is not only permitted but encouraged. Directors must have the freedom to consult independent experts—whether legal, financial, or technological—without it being interpreted as an act of disloyalty. They must be able to challenge each other’s assumptions without fear of undermining management. And they must model the same resilience and openness they expect from executives.

Technology as an Enabler

Amid all the talk of governance, Mr. Sonnenfeld does not ignore the role of technology. During the pandemic, many firms began experimenting with new forms of digital engagement, from weekly CEO forums to open Q&A sessions that flattened hierarchies. Rather than reverting to old habits, he believes boards should seize the opportunity to institutionalize these practices.

“Some CEOs started doing Sunday morning calls during COVID—anyone could log in, ask a question, hear directly from the top,” he recalls. “Many large firms found those forums so valuable they kept them afterward. Technology can be a powerful way to maintain continuity, keep directors informed, and reduce the pressure on quarterly meetings. If used well, it can actually lighten the cognitive load rather than add to it.”

The key is to ensure technology is used to enhance accessibility and transparency, not as another layer of bureaucracy. A steady flow of updates prevents the fatigue that comes from trying to reconstruct conversations months later. It also reassures directors that they are not being manipulated with shifting metrics or goalposts. “If you wait three months between meetings and then see the charts relabeled with different benchmarks, you start to wonder if you’re being played,” he says. “Technology can close that gap, sustain trust, and prevent the erosion of confidence that fuels burnout.”

Character (Still) Counts

Even with better meetings, more transparent processes, and smarter use of technology, Mr. Sonnenfeld cautions that no set of routines will ever fully shield leaders from disruption. The world is too unpredictable, crises too varied, threats too novel. What matters most, he argues, is the character of the board.

“Consultants, academics, and lawyers like to create routines to protect boards,” he says. “But in reality, it’s not the routine that insulates you from the unknown. It’s the character of the board. Crises are more common now—technological disruptions, customers turning into competitors, geopolitical shocks. You can’t anticipate them all. What you can do is build a board with the character to respond with candor, adaptability, and courage.” Here, he draws on an unlikely source: Alexis de Tocqueville. When the French jurist traveled to America in the 19th century, he was struck not by the tightness of U.S. laws but by their looseness—the way they allowed for flexible interpretation and adaptive governance. Boards, Mr. Sonnenfeld suggests, must adopt a similar posture: guided by principles, not shackled by scripts.

“You don’t need an AI protocol that spells out every contingency,” he says. “You need a board that knows how to respond when the unimaginable happens. Because it will happen. The question is not whether you have the right checklist; it’s whether you have the right culture.”

A Mandate for Directors

The implications are clear: boards that want to protect leadership capacity—and, by extension, safeguard enterprise value—must see burnout not as a peripheral concern but as a core governance responsibility. By redesigning meetings to eliminate waste, challenging rituals that sap energy, watching vigilantly for signs of fatigue, and encouraging candor and connection, they can cultivate the character to adapt when disruption strikes.

Mr. Sonnenfeld frames it not as a matter of compassion, though compassion certainly matters, but as a matter of performance. “When leaders are burned out, they don’t think clearly, they don’t take smart risks, and they don’t inspire their teams,” he says. “That’s not just their problem. That’s a governance problem. Boards that ignore it are failing in their duty.”

In an age where the pace of change accelerates relentlessly, where crises arrive not one at a time but in waves, the capacity of leadership has become the scarcest resource of all. Protecting it is not optional. It is the board’s mandate.