Clare Smyth’s Recipe for Leadership

Restaurant kitchens are notoriously macho workplaces. From the grueling scenes in Anthony Bourdain’s book Kitchen Confidential to the prolific swearing in Gordon Ramsay’s TV show Kitchen Nightmares, the kitchen has become synonymous in pop culture with a Darwinian style of leadership. The weak are sniffed out and quashed in the quest for perfection.

Clare Smyth spent many years cutting her culinary teeth in this kind of environment. She worked in militaristic kitchens that were “run on adrenaline and fatigue. It’s survival of the fittest.” At the start of her stint running London’s Restaurant Gordon Ramsay, in 2002, Ms. Smyth recalls that Mr. Ramsay told her she would not last a week in the kitchen. (He was wrong—she worked her way up to become chef patron of the Michelin-starred restaurant from 2012 to 2016—the first woman to run a restaurant with three stars.)

But the culinary world is not the only industry where a bruising leadership approach dominates, Ms. Smyth notes. Highly competitive industries, from journalism to banking, are all guilty of sustaining combative workplace cultures, she says. “It’s pretty much been that way at the top end of most industries. But the world’s moved on quite a bit. If you don’t change, you’re going to be left behind.”

Ms. Smyth is happy to leave behind celebrity chef stereotypes. She is mild-mannered and chooses her words carefully. And she shies away from controversy. When she was named Best Female Chef at the World’s 50 Best Restaurant awards gala in Spain last year, Ms. Smyth accepted the prize graciously but admitted to finding the category “strange,” since gender plays no part in the job of a chef. Her measured ambivalence, even as many of her peers vocally criticized the category as sexist, signals her modus operandi. Ms. Smyth is unapologetically ambitious, but she is not here to ruffle feathers—she is here to cook. And maybe redefine her industry at the same time.

Leading Against the Grain

Raised in rural Northern Ireland by a farmer and a restaurant waitress, Ms. Smyth has worked in some of the world’s best kitchens: Le Louis XV in Monaco, The French Laundry in California and Per Se in New York. She catered Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s royal wedding.

But her first solo venture, Core by Clare Smyth, is making Ms. Smyth’s biggest imprint on her industry. In London’s Notting Hill neighborhood, the cozy spot was named Best Restaurant at the GQ Food and Drink Awards last year. It received two Michelin stars in 2018, just one year after its opening. But Core distinguishes itself beyond food and accolades. It is proof that a restaurant can excel with a leadership style that cuts against the industry’s grain.

But her first solo venture, Core by Clare Smyth, is making Ms. Smyth’s biggest imprint on her industry. In London’s Notting Hill neighborhood, the cozy spot was named Best Restaurant at the GQ Food and Drink Awards last year. It received two Michelin stars in 2018, just one year after its opening. But Core distinguishes itself beyond food and accolades. It is proof that a restaurant can excel with a leadership style that cuts against the industry’s grain.

Ms. Smyth believes in coaching and coaxing talent out of people, not berating and beating them down. Describing her 43-person staff at Core, she says: “People smiling is a really important thing for me. People being happy and everybody being valued as a human being is No. 1.”

She regrets her own management style at the start of her career. She was just 28 when she took the helm at Restaurant Gordon Ramsay, then the only three-star restaurant in the country. “I was under tremendous amount of pressure. I felt that I had big shoes to fill and that I really had to prove myself in that role,” she says.

She never took a sick day or admitted to being injured, and says she overreacted when team members made a mistake. Being the only woman in the kitchen made her feel that she couldn’t show any signs of weakness. It didn’t help that her boss’s celebrity persona included such declarations such as, “Women can’t cook to save their lives,” even as a woman was running one of his kitchens. (Ms. Smyth maintains close ties to Mr. Ramsay, who helped her navigate the world of permits and construction when she was building Core. He continues to support her as a mentor.)

She has decided to lead her own kitchen in a more gentle manner. “I grew up a little bit and realized that you could do it differently,” she says.

“Empathy brings a lot of loyalty to the team. If people feel that you care about them as people, they’re going to give you more back as a person.”

—Clare Smyth, chef and owner, Core

Change in the #MeToo Era

Culture has shifted since Ms. Smyth started, both in broader society and in the kitchen. The #MeToo movement has shone a light on how male-dominated workplaces, including restaurant kitchens, have penalized women and held them back. Among the more high-profile cases was Chef Mario Batali, who announced the closure of his restaurant La Sirena in New York City after being accused of sexually harassing and abusing women who worked for him.

Female chefs are more motivated than ever to drive a change in kitchen culture, and Ms. Smyth says their male colleagues are right there with them. Constant burn-out affects everyone and has contributed to a widespread skills shortage in the culinary world. “There’s not going to be a future for our industry unless we move forward,” she says. With Core, Ms. Smyth hopes to offer an example of how to do so. For one, there are multiple women in the kitchen. “Having a good gender balance basically just makes a better working environment. It’s much, much healthier,” she says.

It is clear from the Michelin stars that she demands excellence from her team. Dishes are checked multiple times before they are served. Quality control is a major component of the job, as is constantly pushing boundaries and trying new recipes to keep the restaurant on top. But Ms. Smyth has also dialed down the heat in the kitchen, putting the pressure on herself instead. She sees it as her job to equip staff with the tools they need to constantly improve and innovate.

“If you don’t change, you’re going to be left behind.”

—Clare Smyth

Every week, someone is tasked with researching a topic related to food and restaurants and presenting their learnings to the team. The front-of-the-house staff also hosts a daily training with subjects that vary along monthly themes. Such a dedicated focus on training is uncommon, Ms. Smyth says, with just a few restaurants around the world operating this way.

“Everybody complains about our industry having a skills shortage, and the only way to fix that is to do something about it,” she explains.

When hiring, Ms. Smyth looks for individuals who will fit well into the culture she has built. She wants them to respect not just her, but each other, the guests and the food being served. Like all companies, restaurants thrive when the team is cohesive and works well together.

The Power of Empathy

For Ms. Smyth, part of that is recognizing the humanity in the people she hires. She invites them to have fun and to bring their personality to the kitchen. They might cook a meal from their childhood or their culture as a way of sharing a piece of themselves with their peers.

“Empathy brings a lot of loyalty to the team. If people feel that you care about them as people, they’re going to give you more back as a person,” Share on X she says. “It can be very lonely at the top when you don’t have the people around you who believe in what you’re doing.”

That’s not to say she is afraid of letting someone go if they aren’t up to task. One of her biggest mistakes as a manager early on was “thinking that everyone could do everything or that I could make everyone do everything,” she says. “Sometimes people just aren’t ready, and you have to be prepared to say, ‘It’s not going to work out,’ and to do the right thing by those people.”

Given the industry’s shortage of skilled labor, she says it is common for chefs to push people into positions that don’t suit them. “We just push them to do it and they can’t, and then they break and they leave. That’s the biggest mistake.”

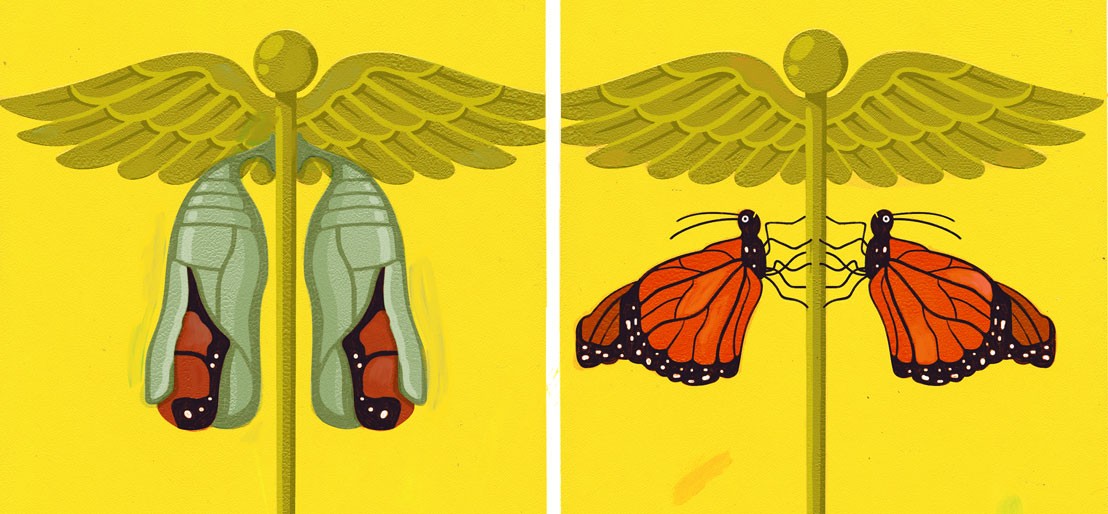

The kitchen at Core operates on a rotation, with people working at one station for three to six months—until they have perfected it—and then moving on to the next. At the end of the two or so years it takes to complete a round, Ms. Smyth lets people go if they want to work elsewhere without burning the bridge. Her willingness to support and respect individual careers has led several past employees to return to her, stronger and more loyal.

When Ms. Smyth hires a promising young woman, she is particularly keen on helping her excel. But she hopes that today’s aspiring female chefs do not have to pressure themselves the way she did at the start of her career. Instead, she tells them to work in the best places they can, and learn from the best—the same advice she gives their male colleagues.

“I wouldn’t advise them to be the way I was,” she says. “I’d advise them to be themselves and to be practical.”