Transformational Leadership Strategy from War and Peace

Before he led the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the end of the Cold War, before he led a massive reform of Texas A&M University and before he became what some have called a “revolutionary leader” of the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), Robert Gates was a leader in Boy Scout Troop 522 in his hometown of Wichita, Kansas.

That was in 1957, when Dr. Gates was just 13. His challenge: Find a way to get other kids to follow him when they faced no real consequences if they chose not to. “I’ve never forgotten it,” says Dr. Gates, now 72. “Nothing develops or tests leadership skills like trying to get people to do what you ask when they don’t have to.”

This early lesson in leadership foreshadowed a central theme of Dr. Gates’ long and celebrated career in public service. Whether he was helming the Pentagon when the United States was fighting two wars or becoming an unlikely advocate for gay rights, Dr. Gates has never been afraid to take uncharted paths—and persuade others to join him. Insigniam founding partner Nathan Owen Rosenberg Sr., who serves on the executive board of the Boy Scouts of America with Dr. Gates, observed, “Bob has a strong moral compass and sense of what will work. Once he sees the right direction, he has an uncanny ability to have others see that direction as the right one and to want to take the journey with him.”

For Dr. Gates, leadership and enterprise transformation go hand in hand. Share on X When interviewing to become president of Texas A&M University, he told the school’s board of regents: “I am an agent of change. If you don’t want change, you don’t want me.”

In his new book, A Passion for Leadership: Lessons on Change and Reform from Fifty Years of Public Service, Dr. Gates contends true leaders must engage in a continuous battle for reform and transformation of their organizations. And that is true whether they are in the public sector, where Dr. Gates spent most of his career, or in the private sector, where he has served on 10 corporate boards, including Starbucks.

“The leadership challenges are very similar in the public and private sectors when you’re aiming at transformational change,” Dr. Gates says. “People, for the most part, are comfortable with the status quo. That affects every organization. And any time you have a leader who believes change is necessary, that leader is going to have to deal with tremendous inertia, with tremendous resistance to change.”

“The leadership challenges are very similar in the public and private sectors when you’re aiming at transformational change,” Dr. Gates says. “People, for the most part, are comfortable with the status quo. That affects every organization. And any time you have a leader who believes change is necessary, that leader is going to have to deal with tremendous inertia, with tremendous resistance to change.”

Few leaders know about overcoming institutional inertia better than Dr. Gates. But, despite the headwinds he often faced, Dr. Gates prevailed—winning rave reviews in the process. The New Yorker dubbed him “one of the shrewdest public servants of his generation.” And staffers in President Barack Obama’s White House, impressed by Dr. Gates’ prescient thinking and adroit leadership skills, nicknamed him “Yoda.”

Building Support

Change does not happen in a bubble. To build support for massive transformation, Dr. Gates says leaders must show respect for subordinates by making them part of the process.

For Dr. Gates, lasting change only occurs after everyone’s voice has been heard. “You have to open the process of change to input,” he says. “Let people have a part. Give them a chance to air their views and opinions. Leaders have to step up and make tough decisions about change, and some people are going to be unhappy. But that’s why the process is so important. Even people who are unhappy will at least feel they were respected enough to be consulted. They will have had a chance to make their case. That mitigates resistance to change.” No matter the role, Dr. Gates made a concerted effort to reach out to all employees.

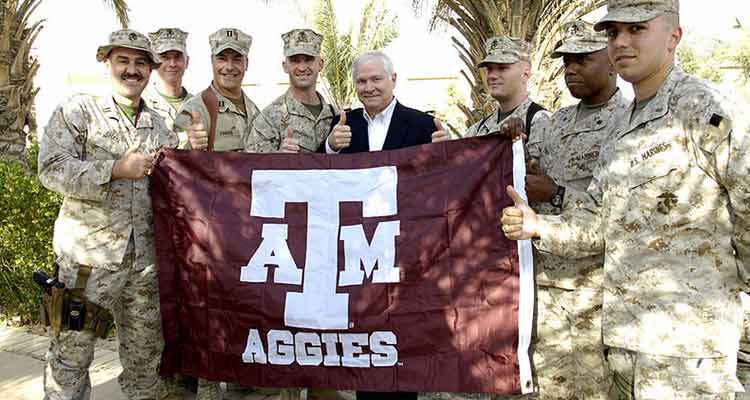

When he was heading the CIA’s analysis division in the 1980s, for instance, Dr. Gates visited with the analysts themselves at weekly brown-bag lunches. As secretary of defense, he would make trips to the Pentagon’s mailrooms and loading docks. The visits came as a surprise to staffers of these often-overlooked areas; he was told no previous defense secretary had ever visited them. And, of course, he went out to the battlefields.

“The people on the front lines probably have a better idea of what’s working and what’s not than anyone else,” Dr. Gates says. “They’re face to face with the customer or with the citizen or with the enemy.”

“When I would visit the front lines in Afghanistan, I would have breakfast or lunch with young enlisted troops or junior officers,” he continued. “I always learned a lot from those sessions because they knew what was and wasn’t working, down to the specific details. That was unlike some of the more senior officers who would paint a rosier picture. And I think nothing matters more in an organization than for people on the front lines to know the people at the top have their back.”

“People, for the most part, are comfortable with the status quo…. [A]ny time you have a leader who believes change is necessary, that leader is going to have to deal with tremendous inertia, with tremendous resistance to change.”

Dr. Gates’ meals with soldiers were not about idle chitchat. He would often assign a lieutenant colonel from his office to take notes during meetings with soldiers and follow up on issues raised. “That way they would know this wasn’t just for show,” he says. “It’s important for leaders, when they do get a suggestion or concern from somebody, to not leave the person wondering whether anybody took it seriously.”

Just as leaders must be accountable for ensuring the changes they have promised will be carried out, engaging employees in a change process means making them accountable for their role in that process. “Leaders have to recognize people who share their agenda and will carry it on,” he says.

“I worked on a project for Bob last year,” Mr. Rosenberg says. “He specified the outcome that he wanted with great detail including by when he wanted it. He then described how he was going to use the work product, painting a picture in words so that I fully understood his intent. That was the end of the conversation, until months later when Insigniam delivered the report. Then Bob was generous in his appreciation for what was delivered. His manner and ways of working inspire—not demand—excellence, having us want to fulfill his intent.”

Power of the People

Along with face-to-face meetings, Dr. Gates often relied on task forces, councils and review groups to empower employees to be part of a change. “Basically, you need an ad hoc structure that breaks down the walls inside an organization and allows people from one part of the organization to criticize another or to express ideas as to how to fix the organizational structure as a whole,” he says. “In every organization I’ve worked at, there were always individuals who had great ideas of how things could work better. But there was almost never a vehicle through which they could express those ideas.”

Virtually every task force he appointed throughout his career “improved on and enriched my ideas and often expanded the scope of the change,” Dr. Gates writes in A Passion for Leadership. It was an ad hoc review group that prompted a watershed moment in U.S. history: the repeal of the U.S. military’s “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, which barred openly gay, lesbian and bisexual citizens from serving.

Dr. Gates, who testified before Congress in favor of the repeal and ultimately oversaw its demise as secretary of defense, convened a review group that gathered information crucial for effectively implementing a repeal and that helped win support for overturning the law.

“A leader has to understand why people feel a certain way if they’re going to make changes,” Dr. Gates says. “But you can’t rely on old assumptions. On ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,’ nobody had ever asked the people in uniform what they thought about the issue. Everything we had was anecdotal. And yet, it was thought that not allowing gays was a fundamental part of the [military] culture. Lo and behold, when [the review group] surveyed 400,000 active duty troops and 150,000 military spouses, much to everybody’s surprise two-thirds said [allowing gays to serve openly in the military] wouldn’t make any difference or that we’d be better for doing so.”

In 2010 the U.S. Congress voted to repeal the policy, and Dr. Gates believes the review group’s work helped change many minds. The alternative was a presidential executive order, which Dr. Gates writes, “would have had a much more divisive and disruptive result, harming those with the most at stake, including military commanders dealing with readiness and discipline issues and gay and lesbian troops seeking to come out in a more tolerant environment.”

As president of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA), Dr. Gates again found himself in the position of leading change for the rights of gays in the United States. In July 2015, fearing potential legal issues, according to The Atlantic, he led BSA’s 80-member board to repeal the ban on gay scoutmasters and volunteers. “I truly fear that any other alternative will be the end of us as a national movement,” he said at the time.

From Hard-liner to Statesman

Forging these connections went a long way in winning over the skeptics.

“I know there were people who disagreed with some of my decisions,” Dr. Gates says, “particularly cutting some of the big weapons programs [at the DoD]. But because they were included, because I listened and gave them a lot of time to talk about their concerns, because I told them where I thought we were headed, and so on, I think—almost uniquely among defense secretaries—I really didn’t have anybody going around me to create problems with the media or Congress or the White House. That was very important to my success.”

But Dr. Gates learned that lesson the hard way.

In 1981, at the age of 38, Dr. Gates was promoted to his first senior position in the CIA. He was put in charge of the analytical side of the agency, a division with several thousand people. Within days of his appointment, Dr. Gates assembled most of those people in an auditorium to announce the changes he intended to make in how foreign-threat analyses would be conducted under his leadership.

“I then proceeded to tell them all what they had done wrong, where they had fallen short and how we were going to do things differently in the future,” Dr. Gates says. “I immediately antagonized everybody who worked for me, even the people who agreed with the changes I’d proposed.”

Despite the fact that many of Dr. Gates’ dictates were eventually implemented (and even deemed necessary), he says resentment smoldered for a long while. “I learned a powerful lesson from that meeting, and never repeated that mistake. You can’t just parachute into the top job and say, ‘I’ll fix this, follow me.’ Share on X That’s going about it with a ‘ready, fire, aim’ attitude.”

So Dr. Gates reinvented himself over time as a leader, morphing from a “brash and sometimes obnoxious young hard-liner” into a “cool-headed elder statesman,” as the New Republic once reported. But he was never a pushover.

After President-elect Obama asked Dr. Gates to remain on as secretary of defense, Dr. Gates assembled teams of analysts to conduct an extensive review of the $500 billion defense budget. The results of that analysis were laid out in Dr. Gates’ 2009 budget address. It included eliminating, scaling down or capping nearly three-dozen major programs, such as the highly touted F-22 Raptor fighter jet and the Future Combat Systems program. At the same time, Dr. Gates requested more money for drones and designated more funding for helicopters and maintenance crews, cyberdefense training and theater missile defense. These changes represented a fundamental shift in focus from preparation for the large-scale conflicts expected in the Cold War era to the “asymmetrical conflicts” against terrorists and insurgent groups that define the contemporary era.

Some of the changes—especially to programs like the F-22, a favorite among some Air Force leaders—sparked anger among a few members of the top brass. But that did not faze Dr. Gates. “I believe trying to achieve consensus on the path forward should be a very low priority,” he says. “If consensus is what you’re after, you’re never going to get significant change. You’re going to get the lowest common denominator.”

Beyond the Status Quo

Ask Dr. Gates what he is most proud of in all of his years of public service, and he does not hesitate: “working to save the lives of our troops.” But even while pushing for such a worthy goal at the DoD, Dr. Gates discovered how many people are biased toward the status quo.

For instance, when he worked to halve the average time it took to fly wounded soldiers by helicopter from combat areas to field hospitals from two hours to one, top military advisers said the time reduction was not necessary because the additional costs associated with the project (more field hospitals, helicopters, crews and hospital staff) would not necessarily save more lives. But according to Dr. Gates, all the information and numbers presented by his opponents failed to account for morale, which is why he overruled them.

Dr. Gates says this is proof that “even if the issue at hand is literally a matter of life and death, the answer is almost always that ‘things are just fine as they are.’”

Most leaders do not face issues of life and death, of course. But in a rapidly changing business environment, a growing number will have to deal with challenges that could ultimately prove the downfall of—or lifeline for—their company. Dr. Gates’ remarkably long and varied career is testament to the fact that no matter the organization or sector, “it is the job of a leader to push for change.”