Leading for Explosive Growth

Peter Drucker boldly declared that “business has only two functions — marketing and innovation. Marketing and innovation produce results,” Drucker wrote in his seminal 1954 tome, The Practice of Management. “All the rest are costs.”

The world of business has changed a lot in the 61 years since Drucker published those words. But he is still right. Executives who boost innovation or improve effective marketing — and especially those who succeed in doing both — are the leaders who will help their companies achieve explosive growth.

But that kind of growth also requires that leaders build on the inherent strengths of the enterprise to create a proprietary process for creativity and execution. To create a system that leads to better innovation and more successful marketing, executives must first know how to overcome factors inherent in organizations that all too often limit the business’ ability to grow.

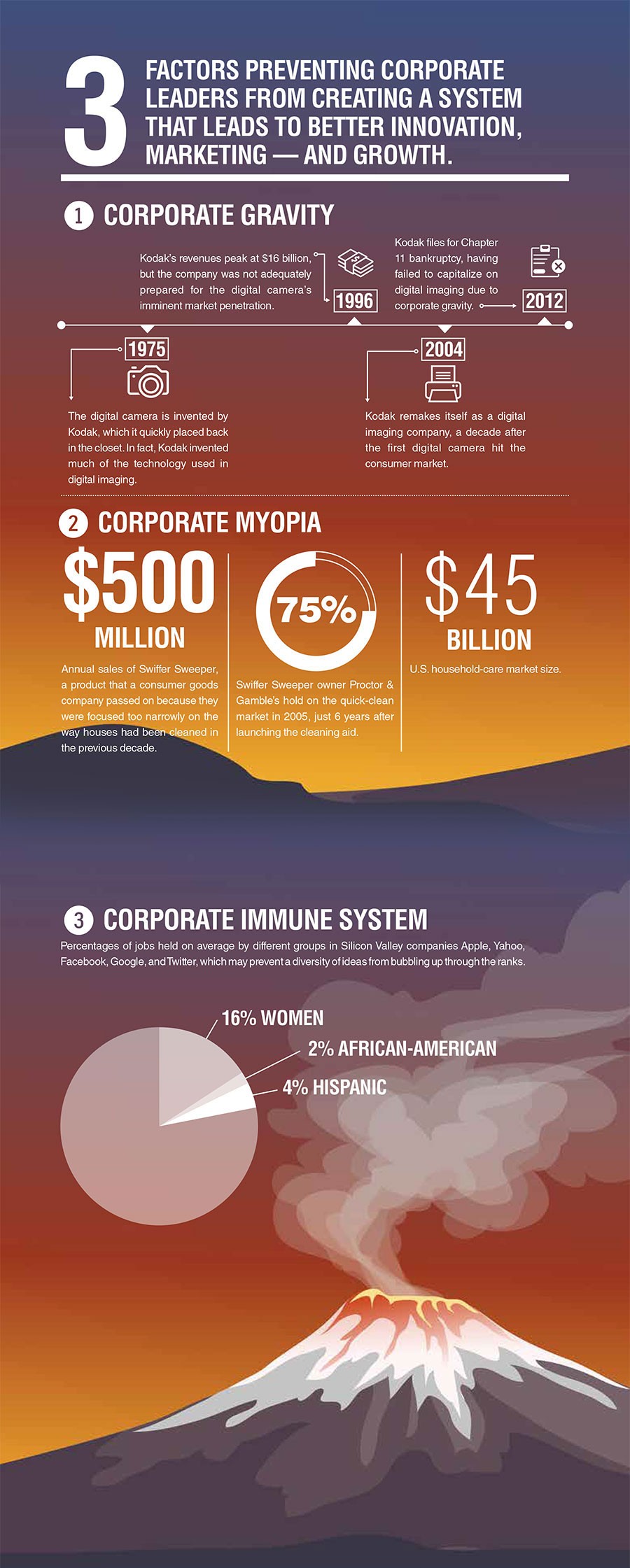

1. CORPORATE GRAVITY

Kodak knew film, and it did film very well. It created the industry for personal cameras. But the company did not anticipate when or how quickly the market — the very market it generated and led — would move to digital. The reason: Kodak was caught in its own corporate gravity; it was stuck in an orbit around a core product.

Too many companies find themselves in similar situations. They develop a core product or service, one that produces a growing income stream that supports much of the company. Understandably, then, companies organize themselves around that core, setting up rules, structures, and systems to protect it and keep the income stream flowing.

But once the business model is organized around that core product or service, management may begin to perceive change — specifically, change that could launch them into new markets or create new business models that eat into the core business model — as threats. Stray too far from the core, the thinking goes, and you might end up cannibalizing or even destroying the source of the enterprise’s success.

In practical terms, corporate gravity might occur when a chief financial officer sets hurdle rates for investments that are too high for most innovations to clear. To be sure, high hurdle rates will protect the core product. And while it is easy to calculate the value of an improvement to the core product or service, the CFO may get conservative when calculating returns on a new way of doing business. That often unrecognized prejudice will weigh down innovations so that they never get off the ground and find their true value in the marketplace.

Arbitrary decision-making has the same impact. Insigniam recently worked with one company that wanted to accelerate new product launches. It had been debuting one new product every two years and wanted to dramatically change that by unveiling one new product per quarter. That required a substantial amount of product testing. But after a few months the testing ground to a halt. Why? Because the company president ignored the test results and made the call on which new products would make it to market. As a result, the employees saw no reason to champion new ideas, because there were no guidelines for knowing whether their ideas had a chance of ever being produced.

Even when guidelines are in place, corporate gravity can weigh down the creative process. For example, we consulted with a pharmaceutical company recently that experienced a drop in market share for one of its major products to No. 2 from the No. 1 position, and other products were beginning to falter. We discovered that the CEO had recently established a regulatory review panel. The team’s primary task was to make sure the company never again ran afoul of regulators. That task may have been a worthy one.

But to achieve it, the review panel swung to a “no risk is the best risk” policy and simply killed most new marketing initiatives that came before it. While not intentional, it had the effect of stopping any new creativity and the potential innovation that could follow.

2. CORPORATE MYOPIA

When a company is unable to recognize future value, it has developed corporate myopia. This short-sightedness may spring from judging value in a time period that is too immediate or from the inability to see value through the customer’s eyes. It is a dangerous condition. When companies can only see what’s in their immediate future and that which only relates to their current mix of products or services, they fail to envision revolutionary new ideas on the marketing or innovation side. That leaves room for competitors to step in.

A consumer goods company lost a rapidly growing category that currently generates about $500 million in annual sales due to corporate myopia. The company had the technology for what would eventually be sold as the Swiffer Sweeper. But they could not see the value in a product because they were focused too narrowly on the way that houses had been cleaned in the previous decade. Once the company passed on the Swiffer concept, a competitor bought it, redefined household cleaning, and created a new product franchise.

3. CORPORATE IMMUNE SYSTEM

The human immune system works hard to kill off foreign bodies, the things that might hurt us. Organizations do that, too, working to kill off dangers of all kinds. That is sometimes good. But occasionally the corporate immune system simply attacks anything unfamiliar, even ideas that could breath new life into the organization.

Take the diversity issues now facing many Silicon Valley firms for example. The workforces at the top tech companies are mostly comprised of white or Asian men. In 2014, Google, for instance, employed more than 46,000 people, but just 2 percent were African-American. Inside Google’s tech division, more than 80 percent of workers were male and 60 percent of them were white. Apple, Yahoo, Facebook, and Twitter have all recently reported similar numbers.

“WHEN COMPANIES CAN ONLY SEE WHAT’S IN THEIR IMMEDIATE FUTURE AND THAT WHICH ONLY RELATES TO THEIR CURRENT MIX OF PRODUCTS OR SERVICES, THEY FAIL TO ENVISION REVOLUTIONARY NEW IDEAS ON THE MARKETING OR INNOVATION SIDE. THAT LEAVES ROOM FOR COMPETITORS TO STEP IN.”

The problem, many think, is not outright racial or gender bias on behalf of the top tech firms. In fact, the point is not gender or race; it is diversity of experience that will lead to new and better ideas. In this case, the thinking is that Silicon Valley executives and managers simply tend to recruit workers who come from the same backgrounds as themselves and have the same perspectives and styles that the executives and managers themselves exhibit. Leaders in all kinds of companies suffer from that same kind of indirect bias when they hire people who resemble themselves in one way or another.

That is what a corporate immune system does: It simply tries to replicate the sources of its prior success and all too often views anything new as a potential threat to future success. That’s a force that can greatly inhibit innovation and growth.

Inspire Creativity and Growth

Leaders who want to avoid the inherent problems with the corporate immune system, corporate myopia, and corporate gravity will want to create a process that identifies factors that inspire creativity and growth and identifies ones that inhibit creativity and growth. That method can take any number of forms, but whatever the shape, it must do three things: embrace risk, create a process for creativity, and measure the creation of value in ways other than traditional profit and loss statements.

Embrace Risk

Wayne Delker, the just-retired chief innovation officer at Clorox, has long managed a massive portfolio of R&D projects, many of which are product redesigns. That could involve anything from putting grooves in Kingsford charcoal briquettes to reduce the weight of the bag and make the charcoal to burn hotter to inventing a product like the ToiletWand. “We have to simultaneously innovate across those different product lines to keep the brands healthy,” Delker said recently.

Clorox executives do not always know that a new product will connect with consumers. After all, before the ToiletWand, with its disposable sponges preloaded with Clorox Toilet Bowl Cleaner, hit the market, consumers had spent decades using wire-and-bristle-capped toilet brushes. Who could say, then, that the wand would be something millions would embrace?

That uncertainty and the risks associated with it did not stop Clorox, because the company trusts what Buckminster Fuller called the “profound knowledge” of its leaders, and it has a proprietary process to bring new technologies and ideas to the market while managing Clorox’s exposure to risk. The most common mistake in regard to profound knowledge is that it presents itself as gut instinct about the industry in which you work. And all business leaders have been traditionally trained to ensure that facts triumph over gut. Leaders who are in the marketplace stand in the stream of their industry every day, with information and data flowing by them constantly. Sometimes all the data, facts, and projections one would like to be working with prove too fluid to capture. But these leaders of growth know what is out there when they have been standing in that stream long enough. The judgments made based on knowledge and wisdom gained from sustained engagement in the marketplace (even if the leaders cannot fully articulate the basis of the judgments) often turn out to be better grounds for a business decision on a new product or marketing approach than a BASES score.

Create a Process for Creativity

Cultivating creativity is bigger than a suggestion box. Companies have to invest in an infrastructure that fosters innovation and gives creative ideas an outlet. Employees have to know how to take an idea and turn it into a prototype and how to move that prototype to a new product or marketing campaign.

One example that worked for one of Insigniam’s clients: Create an office of project management and pair it with an office of project acceleration. Combined, the two are able to push a larger number of ideas through the corporate pipeline. The new innovation office created and published a proprietary innovation process that anyone and everyone in the enterprise can use.

However the infrastructure is set up, execution is key. And execution requires a culture that is focused on accountability. That does not mean “blame, shame, and credit.” Instead, accountability is a system of measuring outcomes. Just like in accounting where your balance sheet must add up correctly, there also has to be a balance in performance accountability. Think of it like this: Producing the intended result is a product of action; accountability is acknowledging the actual result and the actions taken or not taken.

Create a New Scoreboard

Balance sheets and income statements are important. But those agreed-on financial tools do not measure or show valuable developments in innovation and marketing. And, as anyone reading this article will know, the first rule of management is that you tend to get what you measure. Therefore, leaders of growth will have a metric and a scoreboard that measures, captures and displays the value generated by innovation and marketing. What is tracked and displayed on this new scoreboard is critical.

Do you value lead times? Quality control? Brand recognition? Then put those on the scoreboard. Wayne Delker invented a metric to measure ROI for R&D and reported the number at executive team meetings, just as the CFO reported earnings.

Peter Drucker first told us 61 years ago, the two and only two functions of a business that generate value are innovation and marketing. Growth leaders provide an environment that supports creativity through culture, processes, and structure, and have ways to account for the value generated by that creativity.