Success Guarantees Nothing

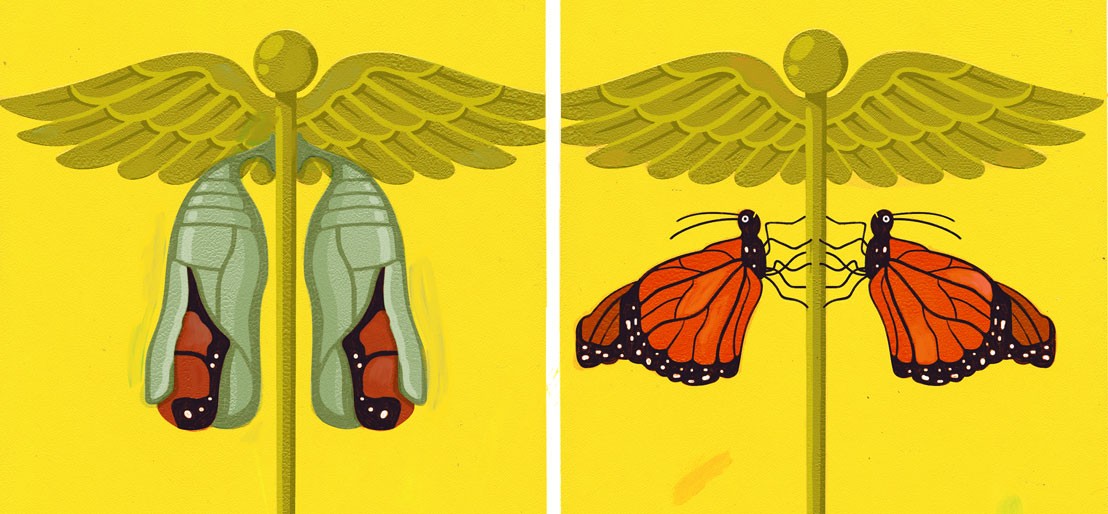

If you are enjoying unprecedented success, now is not the time to accept slaps on the back. Regardless of current performance, if the rate of change inside your organization is not equal to or greater than the rate of change in the marketplace, your company is already going out of business. You just have not realized it yet.

Across more than three decades of consulting, I have found that the best predictor of future failure is current success. This paradox results from three factors that thwart the bold thinking necessary to continually innovate in a tumultuous world.

The first stumbling block is what I call corporate gravity. Much like physical gravity, it is an invisible force that tethers employees to a company’s traditional way of doing business. When coffers are flush, this gravity masquerades as common sense: It protects current sources of profitability. Why change what is not broken?

The second problem is corporate myopia: the inability to recognize something of value outside current products and services. Again, when you are on top of the world, it is easy to become shortsighted and allow the urgency of today to supersede the importance of future business. Share on X

The final ailment that afflicts the successful involves what I call the corporate immune system. In much the way that antibodies in our own immune system attack perceived threats, the corporate version has practices that fight back against the perceived damaging effects of change. However, just as our bodies can overreact, leading to dysfunction and disease, corporate immune systems can also overzealously guard against attempts at innovation.

Sears vs. GM

To understand how all three factors can spell disaster, look at Sears, which filed for bankruptcy in October. From its origins selling watches to 19th-century farmers, Sears, Roebuck and Co. grew into a corporate behemoth that anticipated—and profited from—major cultural shifts including the rise of the automobile and ensuing suburban sprawl. Eventually it stopped innovating and began focusing on protecting its success by repeating what had worked before.

As recently as the 1990s, Sears was still a department store colossus. But as big-box newcomers began stealing customers, Sears tried to fight back by doubling down on large physical stores rather than looking to the future and anticipating the internet’s revolutionary impact. The company’s 2005 merger with Kmart, another old-school retailer, did not change this dynamic.

Sears’ downfall proves that every company’s systems and practices are inherently historical artifacts. Yet top-performing companies do not face inevitable ruin. Organizations that maintain rigorous processes for reinventing strategy can stay ahead—or come back after a period of decline. An example: General Motors, the 20th-century juggernaut that emerged from bankruptcy in 2009 only with the help of a taxpayer bailout. Today, the auto company is one of the two global leaders in self-driving cars.

General Motors managed to change before it was too late. For too many other companies, the complacency bred by success is a death sentence.