The Ever-Evolving Culture of Boards

Now more than at any other time in modern business history, the culture of the boardroom is evolving Share on X. Increased scrutiny in the form of stakeholder activism and government regulation is forcing shifts in three key areas: whom the board serves, its role in execution and its structure. And while it is hard to predict exactly where these changes will lead, one thing is clear: In the end, the mindset and makeup of boards will not look the same.

Whom Do Boards Serve?

Stakeholders or shareholders? For years, business leaders, academics, economists and even governments have debated which should be the primary concern of a corporation’s board of directors. But in practice, a board’s focus is often determined by where the company is located.

In the United Kingdom, Australia and the United States, for instance, companies have a long-standing tradition of adopting the shareholder model of corporate governance. The board’s primary job is straightforward: Represent shareholders’ interests by maximizing profits and setting direction. Companies in the rest of Western Europe and many in Latin America, on the other hand, tend to build their corporate governance approaches around the stakeholder model. Boards are typically more concerned with the interests of many parties—customers, employees, creditors and the community at large, as well as shareholders.

“European boards spend a lot of time looking at the accounts in detail and looking at stakeholders as well as shareholders. Their time is more split between strategy and ongoing [operational matters] that in the United States are more in the hands of the executives.”

—Michel de Fabiani, vice president of the Franco-British Chamber of Commerce and Industry

“European boards spend a lot of time looking at the accounts in detail and looking at stakeholders as well as shareholders,” says Michel de Fabiani, vice president of the Franco-British Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Also former chairman and CEO of BP France, he serves on the boards of Valeo, Ebtrans Luxembourg, Valco and BP France. “Their time is more split between strategy and ongoing [operational matters] that in the United States are more in the hands of the executives.”

The pendulum seems to be swinging away from the shareholder-centric modus operandi, though—especially in the United States. Writing on The Huffington Post last year, Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff signaled why: “The business of business isn’t just about creating profits for shareholders—it’s also about improving the state of the world and driving stakeholder value.”

Throw Out the Rubber Stamp

In KPMG’s September 2015 Global Boardroom Insights, 80 percent of the 1,000 responding directors and senior leaders from around the world said that over the past two to three years their board had deepened its involvement in not just the creation of strategy, but also the monitoring of its execution, the consideration of strategic alternatives and the recalibration of strategy as needed.

Examples abound for why this change is occurring.

Take Australia-based supermarket giant Woolworths. Facing increased competition from rivals Aldi and Wesfarmers-owned Coles, then-CEO Michael Luscombe pushed Woolworths into the hardware business. Starting a hardware chain (which the company ultimately named Masters) would boost the bottom line, Mr. Luscombe said, while simultaneously striking a blow to Bunnings Warehouse, a leading hardware store chain also owned by Wesfarmers.

But the plan backfired. Instead of seeing a drop in market share, Bunnings continued to expand. In January, the company announced it would purchase U.K. home improvement chain Homebase. The same month, Woolworths announced it would close all 63 of its Masters stores. The failed chain has seen combined losses of more than AUD600 million, according to The Australian Financial Review. That includes a loss of AUD245.6 million in fiscal year 2015, according to Woolworths’ financial reports.

“The business of business isn’t just about creating profits for shareholders—it’s also about improving the state of the world and driving stakeholder value.”

—Marc Benioff, CEO, Salesforce

What went wrong? Critics say Masters suffered from poor product choices, inconvenient locations, high prices and a marketing campaign that alienated instead of attracted the tradesmen who comprise Bunnings’ core customer base. But ultimately, critics point to the Woolworths board of directors’ insufficient engagement with monitoring execution and its inability or unwillingness to change course when the initiative showed signs of failing. “When you look at who’s accountable, the board has ultimate responsibility for the management, direction and performance of a business,” Alex Malley, CEO of CPA Australia, wrote in The Australian Financial Review.

With the board’s backing, for nearly five years the company poured money into a strategic error. “At what stage was there enough light shone on the strategy by the board when there were doubts about it?” fund manager John Sevior asked in another Financial Review article. “… [A]t what point do you put your hand up and say we’ve got this wrong?”

In the end, both the CEO and board chairman who oversaw the failed Masters gambit resigned. Several other board members who served during that time followed suit, making way for the new chairman to reinvigorate the board with fresh blood.

Major missteps are not the only factor driving boards’ increased role in strategy and execution, however. Greater shareholder engagement is also playing a part, says Walt Rakowich, former CEO of Prologis, current lead independent director of Host Hotels & Resorts and chairman of the audit committee at Iron Mountain. “It’s nothing for an investor to call a board member today. That never happened in the past,” he says. “I see a lot more involvement. The world is an open book. That’s the power of the Internet and social media. Boards have faced far more scrutiny over the last couple of decades. They’re not there to rubber stamp. They’re truly there to govern and provide advice to the company.”

It is a change that is also reflected in how board members, at least in the United States, prepare for meetings. “Seventeen years ago, when I was in my first board meeting as CFO of a large public company, I would say maybe half the board members didn’t really read the materials before the meeting,” Mr. Rakowich says. “Now I prepare at least eight to 10 hours before all board sessions.”

Mr. Rakowich notes that board meeting books when he started were maybe 30 pages long; now they are the size of a major-metropolitan-area phone book. That indicates both management and the board are putting a lot more time into preparing for each meeting.

That preparation, along with committee meetings, has increased collaboration between board members and management, particularly around strategy, capital allocation, risk and talent management, and communications, he says. “I think there is a lot more collaborative discussion between management and the board surrounding these objectives than there has been in the past. That change is certainly better for everyone.”

Independence Wanted

Board independence is continuing to garner more and more attention around the globe as shareholders call for boards to fight for their interests above the CEO’s, and as governments look for more corporate transparency and accountability.

One response to this pressure has been the addition of more independent directors to boards. According to a report from EY, as of 2014 more than 90 percent of Fortune 100 boards had some form of independent board leadership. In many countries, the push for more independence is being led by government regulation. Last year, for example, Japan’s government established a Corporate Governance Code for all companies listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, mandating that they add at least one independent director to their boards.

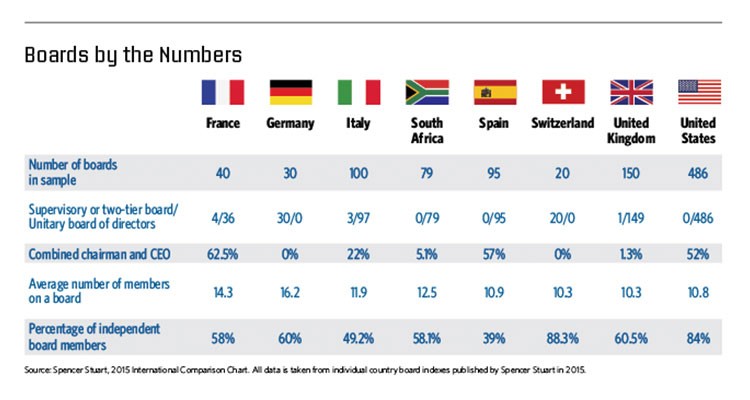

But the prevalence of such independent board members varies by country. Public boards in the United States differ from those in Europe or Asia in that the U.S. boards have almost all independent directors, with only one or two insiders, according to Robert Pozen, senior lecturer at MIT Sloan School of Management, independent director of Medtronic and Nielsen, and chairman emeritus of MFS Investment Management.

That said, boards in some European countries are far more likely to be headed by an independent chairman, Dr. Pozen says. In the United States, the CEO is frequently also chair of the board. The trend is starting to shift slightly, with EY reporting that 41 percent of Fortune 100 companies have separated the roles of chair and CEO. But even in those cases, only 27 percent of the chairs are independent.

At the same time, independence in theory does not mean independence in practice Share on X, Dr. Pozen says. “Some people would argue that having an independent chairman lets the board hold the CEO more accountable,” he says. “Other people would argue that the lead independent director could play the same role. I think it’s a functional matter. It depends on what roles they actually play and the personality of the people.”

In the end, there is no ultimate right or wrong for how boards should be built. “The personality and culture of the board to me is more important than how many independent directors it has,” Mr. de Fabiani says. “If there’s trust, there’s likely to be good collaboration and open communications. That’s not to say they have to be collegial. There can be a lot of harsh decisions, but if they trust each other to make the right decisions, a lot can get done.”