A Healthier Way to Lead

They were exhausted, but, as it turns out, the work was not done just yet. In late February, the 82-person Cone Health Hospital team in Greensboro, North Carolina, had finished a sprint to move office supplies, medical equipment and patients from a stand-alone women’s hospital into a brand-new $100 million women’s and children’s tower at the main campus across town. The painstaking process took four years to plan, four days to move equipment and supplies, and four hours to relocate 102 patients from Cone Health’s former women’s hospital to the new facility. The execution was nearly flawless.

“It was really a breakthrough,” says Karin Henderson, RN, BSN, MSN, CCRN, CENP, EDAC, executive director of Strategic Management at Cone Health, who led the hospital construction and the moving team.

But 11 days later, the same team—which included staffers in finance, maintenance, IT, nursing and other departments—was called back to take on another project that would have seemed cruel in its urgency had the cause not been so important: repurpose the now-empty 200,000-square-foot women’s hospital into a facility for COVID-19 patients.

“Would the wiring be able to withstand adult ventilators? Would the air-handling systems work if we changed the entire hospital to negative pressure, which was key to taking care of the patients? That building was humming with energy. I mean, it was unlike anything I’ve ever seen, as far as a renovation project goes,” Ms. Henderson says.

They finished the work in 28 days.

A Need for Change

Managing change borne of black swan events like the pandemic is what the executive team at Cone Health has been training for for nearly 10 years—only they did not know it. Their journey began with the simple intent of moving from middle-of-the-pack industry performance to being a national leader in health care as measured by industry benchmarks.

“If we went back 10 years, we were a very top-down organization, focused on our financial outcomes and probably a little less focused than we should have been around our employee engagement, involvement and empowerment,” says Dr. Debbie Cunningham, DNP, MSN, RN, senior vice president for Behavioral Health & Women’s and Children’s Services. “So, at that point, we engaged in very intentional work to change that and move finances to the back, bring our patient-centered care to the forefront and empower our employees.”

Winning By Caring

“The executives and representatives from key stakeholders in the health system came together and confronted the key drivers of their culture,” says Insigniam partner Jennifer Zimmer. “If they were not going to be driven merely by financial performance, then what would they drive?”

“I won’t say we had outright gender bias, but we all know how difficult it is for women to be in positions of power and influence in a company.” —Dr. Debbie Cunningham, Senior Vice President for Behavioral Health & Women’s and Children’s Services

The organization rallied around three key values:

- Caring for our patients

- Caring for each other

- Caring for our communities

Cone Health also made a bolder patient promise: We promise to be right here with you.

Then they set about asking, “How do we get the best out of everyone?”

“Over my nearly 30 years with Cone Health, I’ve seen a big shift,” says Dr. Cunningham. “I won’t say we had outright gender bias, but we all know how difficult it is for women to be in positions of power and influence in a company. When we started to focus on the value everyone brings to the team, we had a breakthrough.”

A Hospital Made of Cardboard

Typically, when hospitals build a new facility, they bring together leaders and a few frontline staff and ask them what they want or what they think would work. It is not typical for a nurse to head up a construction project. But the leadership at Cone Health was willing to acknowledge that the people who do the work know the work, and that meant that Ms. Henderson—who was a nursing leader—was the right fit for the job.

The leadership sent her and a small team to a hospital in Seattle, where they tested a novel construction approach. They built a single room out of cardboard. On the way back, she wondered if Cone Health could use the same approach and build the entire hospital out of cardboard.

“I went to my leader, Chief Strategy Officer Jim Roskelly, and said, ‘Jim, I need $40,000 and a warehouse, and here is why.’ He didn’t question it,” Ms. Henderson says. “To have a C-suite who’s willing to have somebody make that kind of request shows that the leadership was willing to assess their own points of view to allow different voices to shape approaching things in different ways.”

With a cardboard model in place, Cone Health employees—from frontline secretaries to nurses to environmental services staff—were asked, “Does this work for you?” They simulated patient scenarios and crisis situations, and the staff had the autonomy and the authority to move a wall, cut a hole in a wall or change the location of a doorway.

“They were given markers and asked what would work better. Maybe they’d draw a door in a different location or make some other change,” Ms. Henderson says. “But when they walked into the physical building, the change was there.

“That went miles with staff because this was a collaborative process,” Ms. Henderson says. “It wasn’t the top-down ‘we know best.’ The frontline staff has the wisdom to determine what’s going to work best for patient care.”

Empowered Leaders Create Diverse Leaders

That hospital experience—from the cardboard build to the actual construction and relocation—was part of building and institutionalizing a culture of caring and “being right here with you.” It went from words on a sign to actual drivers of how work was done and the type of care and patient-centric focus that facilities were designed to deliver.

With the pandemic looming, leadership and staff could move with more confidence into the unknown. While the staff worked to get the COVID-19 hospital ready, leadership set the tone and vision for overcoming what they were up against while also removing external barriers.

“I saw the C-suite working with the governor to talk about the importance of social distancing, about when to open or when to close the community,” says Waqiah Ellis, executive director of Heart and Vascular Nursing Services and current chief nursing officer for the COVID-19 facility.

Cone Health’s Chief Medical Officer gave daily updates about the hospital in the context of the pandemic. The transparency in leadership further established a culture of caring and being right with the staff. Share on X

It Takes Too Much Energy to Hold Back

When the 82-person team was called back to convert the empty building into a COVID-19 care center, there was no hesitation.

“They canceled plans. They canceled their vacations. They canceled their time off,” Ms. Henderson says. “They were working night and day, literally seven days a week, to get the building turned around.”

“We have a team that’s here every day, committed to a bigger picture, something bigger than themselves. We’ve built a team full of leaders.” —Waqiah Ellis, Chief Nursing Officer for the COVID-19 facility

The team converted the neonatal intensive care unit (ICU)—with its pod-style environment that previously accommodated babies—into an ICU for adults with COVID-19, Ms. Ellis says, tackling the project like a puzzle.

During the transition, they studied COVID-19 data as the tally of patient cases started climbing. Inevitably, they wondered if they would be faced with the same questions: Do we have enough ventilators? Will we need to decide who gets a ventilator and who does not? Do we have to decide who lives or dies?

“We shed many tears having those conversations,” Dr. Cunningham says. “So we just put it on the table. It’s a scary time, and it’s okay to say, ‘I’m afraid that I’m going to have to make decisions about who goes and who survives.’ How do we, as a team, handle that?”

Being transparent and authentic helps people find a solution when there is no established answer, says Ms. Henderson.

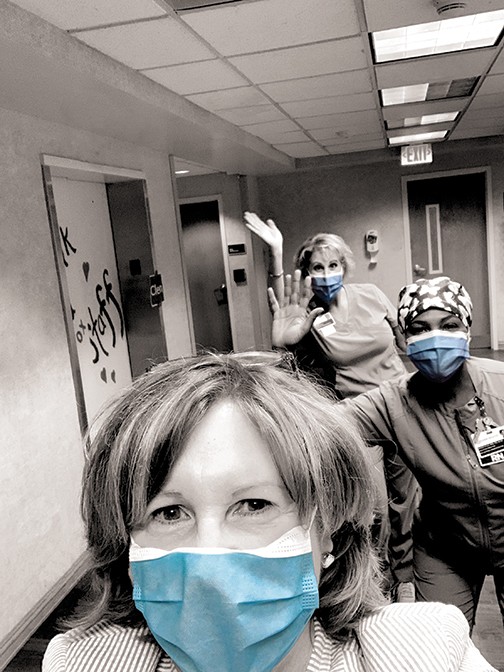

When the new COVID-19 facility was ready to accept patients, everyone looked the same. Nurses, doctors and staff all wore the same uniform: personal protective equipment (PPE) and scrubs.

“I believe that that has had an impact on our team dynamics,” Ms. Ellis says. “It doesn’t matter who the doctor is or who the nurse is. We all look just alike, and I think that has been huge for us.”

The refinement in Cone Health’s culture and leadership has been life-changing. Literally. Ms. Ellis recalls a situation this past summer in which the nursing staff was ready to call a patient’s family to prepare them for his death. Some three weeks later, he was walking around, she says.

“We were not expecting this person to live, but we allowed ourselves to learn through this illness, turn on a dime and be flexible in our decisions. We were able to provide this man with exactly what he needed,” Ms. Ellis says.

“We have a team that’s here every day, committed to a bigger picture, something bigger than themselves. We’ve built a team full of leaders.”

This article appeared in the Fall 2020 issue of Insigniam Quarterly. To begin receiving IQ, go here.