Under Siege: Dealing With Activist Investors

The most feared man in corporate America.

That infamous title was bestowed upon activist investor Jeffrey Smith, CEO of New York-based hedge fund Starboard Value, by Fortune in 2014 after he executed a game-changing proxy fight against Darden Restaurants, which owns chains such as Olive Garden and LongHorn Steakhouse. In a nearly 300-page presentation to shareholders, Mr. Smith and his cohorts at Starboard Value made the case that Olive Garden was poorly run, arguing (among other things) that Darden’s food costs had become some of the highest in the industry while quality had declined.

In the end, Mr. Smith—with the backing of a majority of other shareholders—won the fight and gained free rein to replace all 12 board members and then-CEO Clarence Otis. Though he owned less than 10 percent of the business, Mr. Smith effectively took control of the Fortune 500 company.

This coup d’etat has become a piece of corporate legend. Never before had such a complete boardroom takeover happened at a company as large as Darden. Since then, however, the list of Mr. Smith’s corporate-warfare casualties has only grown. He has infiltrated several major companies he considered to be underperforming, including Yahoo, Office Depot, Perrigo and Marvell Tech. In each instance, his arrival resulted in the ousting of several board members and sometimes even the CEO.

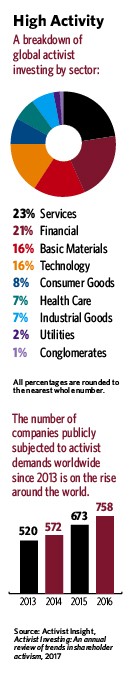

But Mr. Smith is only one activist in an ever-growing pool. According to research firm Activist Insight, the number of companies publicly subjected to activist demands worldwide since 2014 has jumped more than 30 percent—from 572 to 758. Boards and CEOs who fail to deliver value are under threat of being challenged by activist investors Share on Xwho seek to upend the current business model, leadership team or capital structure in order to drive up shareholder value.

“If an activist gets involved, they are directly or indirectly saying the board has failed to uphold its responsibilities.”

—Daniel Romito, senior analyst and head of strategic capital intelligence, Nasdaq Advisory Services

“They come with a plan and a directive to management outlining how to enhance shareholder value,” says Daniel Romito, senior analyst and head of strategic capital intelligence for Nasdaq Advisory Services in Chicago, Illinois, USA. “It’s a much more aggressive, value-driven investment strategy.”

Board members and CEOs who fail to respond could easily find themselves left out in the cold.

A Measured Response

As soon as an activist investor makes it known that he or she has taken interest in an organization, board members should brace themselves. “It’s the board’s job to guide management,” Mr. Romito says. “If an activist gets involved, they are directly or indirectly saying the board has failed to uphold its responsibilities.”

That does not mean digging in your heels, however. “There is a natural tendency to become defensive in these situations, but that plays right into the activist’s hands,” Mr. Romito says. Instead, he encourages companies and their board members to view activist requests as the starting point for intense negotiations.

The activist will come to the company with a plan that may include major shifts, such as spinning off divisions, changing leadership or paying out dividends with reserved cash. In response, the management team—including the CEO—should take the time to understand what the activist wants and why, and then prepare a strategic response, he says. That includes creating various scenarios that lay out which aspects of the activist’s plan are feasible and what the long-term implications of such changes will be for the business, the employees and the stakeholders.

“When the CEO and the C-suite are willing to engage, it becomes a lot easier to work with the activist investor,” Mr. Romito says. “That professional courtesy can go a long way in these negotiations.”

The board should also work with the CEO and other key executives to dissect why the company became a target in the first place, and consider any good suggestions the investor may have for improving the business, says Tobias Carlisle, a Santa Monica, California, USA-based partner at Carbon Beach Asset Management and author of Deep Value: Why Activist Investors and Other Contrarians Battle for Control of Losing Corporations.

He urges managers and boards to at least listen to what activists have to say. “If it’s reasonable, implement it, and if it’s not, explain why,” he says. “It’s a lot easier to make these decisions with management involved than to let activists steer the way.”

Hit the Campaign Trail

But being reasonable does not mean rolling over. The CEO and board of a company under siege should consider launching a campaign to defend their strateg y—and their reputation—to the rest of their shareholders, says John Coffee, the Adolf Berle Professor of Law at Columbia Law School in New York, New York, USA and author of The Wolf at the Door: The Impact of Hedge Fund Activism on Corporate Governance. Most activist hedge funds only acquire 5 to 7 percent of a company’s shares, he says, but as much as 20 to 25 percent if it is a “wolf pack” of investors. “That means the balance of power is still in the hands of the remaining investors.”

y—and their reputation—to the rest of their shareholders, says John Coffee, the Adolf Berle Professor of Law at Columbia Law School in New York, New York, USA and author of The Wolf at the Door: The Impact of Hedge Fund Activism on Corporate Governance. Most activist hedge funds only acquire 5 to 7 percent of a company’s shares, he says, but as much as 20 to 25 percent if it is a “wolf pack” of investors. “That means the balance of power is still in the hands of the remaining investors.”

If management and the board can make a case to the majority shareholder group that their current strategy will deliver long-term business value, they may be able to fend off the activist investor’s plans, or at least gain leverage to force a compromise, Mr. Coffee says.

Take DuPont, for example: In 2015, the U.S. chemical company was able to block activist investor Nelson Peltz’s efforts to replace four members of its board by convincing shareholders to back the 12 directors nominated by the management team. Winning the battle required a $15 million shareholder campaign from DuPont leadership, which explained their plans for retooling the business. Although DuPont did not itemize the specifics of how it spent that $15 million, corporate funds are typically spent on things like hiring law and public relations firms, printing and mailing shareholder letters and ballots, and traveling to meet with investors, according to USA Today. Leaders also focused on securing support from three of the company’s largest shareholders, all of which are index funds.

David Pyott, CEO of pharmaceutical company Allergan, also aggressively fought off a hostile takeover bid from activist investor Bill Ackman and rival pharmaceutical company Valeant in 2014. Mr. Pyott told Fortune that he spent 90 percent of his time that year dealing with the attack, and ultimately won by questioning Valeant’s financial reports and convincing stakeholders that the rival’s business model was unsustainable.“He was right,” Mr. Coffee says. “Within two years Valeant imploded, at one point losing 90 percent of its value after overstating its earnings target by $600 million. Its stock price crashed due to allegations of improper accounting and predatory pricing practices designed to boost growth. Allergan was very lucky it was able to fight off Valeant. This example shows activist investors don’t always win.”

Be wary, however, of where the fight is staged. The biggest reputation hits happen when these deals go public. “If the negotiation between management and activist remains private, the company’s legacy may remain intact,” Mr. Romito says. If the activist involvement gains media attention, it can affect a brand’s or a CEO’s reputation. “While we most often see this take place with the larger Tier 1 activists who approach traditional blue-chip and mega-cap companies, it can occur with small- and mid-caps as well.”

A Corporate Revival

For all the chaos activist investors can create, there are also tales of positive transformation that board members and executives should keep in mind.

Take Darden Restaurants. With his new board and CEO in place, Mr. Smith went about overhauling the company’s Olive Garden brand by tweaking the chain’s menu and kitchen practices, improving alcohol sales and putting an end to the restaurant’s endless breadsticks.

Take Darden Restaurants. With his new board and CEO in place, Mr. Smith went about overhauling the company’s Olive Garden brand by tweaking the chain’s menu and kitchen practices, improving alcohol sales and putting an end to the restaurant’s endless breadsticks.

“Starboard understood the problem, and they turned the restaurant chain around,” Mr. Carlisle says. “That kind of operational success—rejuvenating a once high-performing company in decline—has given rise to more activist investing around the world.”The result has been a 47 percent rise in the company’s once struggling stock value and an increase in year-over-year sales at existing chain locations for six straight quarters, The Wall Street Journal reported last year.

Last year, U.K.-based Rolls-Royce became the first FTSE 100 company to surrender a board seat to an activist. And according to Activist Insight, activism outside the United States in general has surged, “despite the preference for privacy in European and Asian countries, where investment communities are averse to public spats, shareholders do not have stringent disclosure requirements for their plans and most activism takes the form of behind-the-scenes negotiations.”

At this point, the marketplace has grown so accustomed to turnarounds driven by rumors of a takeover or merger that the mere act of making an activist play for a company can drive up its stock price, Mr. Coffee says. He notes that stock prices will often jump the day an investor files with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission announcing they own more than 5 percent of the voting class of a company’s stock. “The market sees that as a sign that the company is in play, which raises its potential value,” Mr. Coffee says. Buffalo Wild Wings, for example, saw its stock price jump 5 percent the day activist investment firm Marcato Capital Management revealed its stake in the company last July.

In the end, “activist investing is just a tool,” Mr. Carlisle says. “There are good and bad activists, just as there are good and bad management teams. The good ones seek to correct issues and can improve the value of the business. Listen to the requests, consider whether they are appropriate for the business and implement those that are beneficial to the company’s long-term success.”