Leading for a Corporate Culture of Design Thinking

Special Section: This special section is adapted from a chapter of Design Thinking: New Product Development Essentials from the PDMA, Wiley-Blackwell, 2015. www.wiley.com

THE CRITICAL IMPACT OF CORPORATE CULTURE ON DESIGN THINKING

Empathy. Ideation. Collaboration. Iteration. These are not the typical terms in the everyday conversations of executives at a large corporation. Instead, top executives are likely to be focused on the top and bottom lines, market share, return on investment, share price and employee retention. But empathy? Not in most big companies.

Yet empathy, ideation, collaboration and iteration are critical aspects of design thinking. For executives who want to install design thinking as a source for their companies’ successes, knowing and understanding terms like this, and the practices and processes behind them, are important for achieving those other key measures of success.

Roger Martin, the former dean of the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto and one of the founding fathers of design thinking (along with the Institute of Design’s Patrick Whitney and Stanford d.school’s David Kelley and Bernie Roth), once wrote that incorporating design thinking into a large company “… is not as simple as hiring a chief design officer and declaring that design is your top corporate priority. To generate meaningful benefits from design, firms will have to change in fundamental ways to operate more like the design shops whose creative output they covet. To get the full benefits of design, firms must embed design into—not append it onto—their business.”1

Embedding design thinking into a business means embedding it into the company’s strategy, corporate culture, processes and practices, systems and structures. For too many large companies, their corporate cultures are obstructive to design thinking at best, and at worst are destructive of this important new business and management method. However, we believe that an enterprise that embeds design thinking in its corporate culture—in its everyday ways of working, its shared practices, beliefs and values—can gain a competitive advantage over those that do not adopt design thinking.

To gain this edge, however, organizations will need to re-evaluate the organizational context in which they currently operate. And here is the Gordian knot: A company’s context is transparent to the people who work in the company.

Culture as Context

The context in which people are working in an organization is primarily the corporate culture. The organizational context influences, shapes, emphasizes, diminishes or distorts everything that happens in an organization. It reinforces the choices executives make to pursue some strategies and discard others. It virtually chooses the tactics by which managers execute. It encourages employees to behave in specific ways and rewards them for it and often can discourage them from, or even punish them for, acting in different or new ways.

Context can be a potent force for change—pushing organizations to continually look for new opportunities—or for stagnation—encouraging organizations to stick to the status quo, failing to recognize changes in the market. Corporate culture can drive innovation to significant value in the market or kill a great idea. Indeed, corporate culture can have one company see an opportunity and another miss or dismiss the same one. In this way, corporate culture is a singular determinant of organizational effectiveness.

When a company chooses to implement a radical or fundamentally new initiative, like embedding design thinking, the success of that initiative is not simply going to be a product of training and education, nor of management telling people what to do and following up, nor even a product of some new compensation or reward system. Implementing a discipline like design thinking will be successful only if it fits in with the corporate culture, even when that means supplanting some elements of the current culture with elements drawn from design thinking.

But transforming a corporate culture is complex, difficult and fraught with risk of failure. Arguably, organizational transformation is one of the most difficult initiatives that a company can undertake, the equivalent of an experienced mountain climber scaling Mount Everest: a long, complicated, challenging journey that is not to be undertaken lightly.

Default Culture

In most companies, culture is not intentional or purposeful. Typically, culture has evolved organically from the company’s founding days, from the personality and likes and dislikes of the founder(s). Like Topsy, it “…just growed.”

Corporate culture is likely to default to reinforcing what has worked in the past and avoiding what has not worked, especially avoiding significant failures. It is a relic from the past that powerfully shapes both perceptions and actions and limits possibilities. It often occurs as a given; corporate culture is the way it is around here. That can be true even when culture had been an intentional creation.

At Ford Motor Co., Henry Ford shaped the culture from the firm’s earliest days to avoid a previous traumatic failure and to cause the company’s success. So important was his influence on the firm’s culture that in the early 1980s—more than three decades after the founder’s death—Mr. Ford’s ghost was said to be walking the halls of the company. Although the auto industry and the methods of manufacturing had changed drastically, Mr. Ford’s culture had not.

By way of example, in 1985, an Insigniam colleague was conducting a training session with both older and younger employees of the Body and Assembly Division of Ford. Each participant was asked to write down something very significant that had happened in their tenure at Ford, something that they had put away in their “silver box of memories.”

An older participant shared that in his first year at Ford, he was in the lunchroom eating the ham sandwich that his wife had made, when Henry Ford sat beside him. The employee said, “Mr. Ford was somewhat of a health nut. He had special bread baked every day, and when he traveled, he had his bread flown to his location. In this instance, Mr. Ford said to me, ‘John, you know that stuff you’re eating is bad for your health. You shouldn’t be eating it,’ and then he rose and walked away.”

Our colleague asked, “What happened next?” Looking a bit surprised at the question, the gentleman said, “I’ve never eaten ham since that day.”

A culture that made Henry Ford a quotable and inspirational industrialist and gave his company a huge competitive advantage had become a barrier to Ford Motor Co.’s success in a much-changed marketplace. Fortunately, his successors, Donald Petersen and Harold “Red” Poling, led the cultural transformation to recover Ford’s competitiveness—the first-known intentional transformation of the culture of a large corporation.

In too many large organizations, corporate culture is a barrier to design thinking and potent innovation. And transforming corporate culture is a particular challenge for executives hoping to move their organizations toward design thinking.

Why do we say this? Design thinking is human-centric—focused on the customer, the consumer or whoever the end users may be. Design thinking requires a high degree of empathy for the end user, as well as big doses of risk taking, prototyping and failing. Therefore, the practice of design thinking is likely to be antithetical to the corporate culture of most large companies, where data-driven decisions, rigid organizational hierarchies, well-established rates of return on investment and a high cost of failure are often the preferred business-as-usual ways of operating.

Impact of Corporate Culture on an Organization’s Ability to Innovate Through Design Thinking

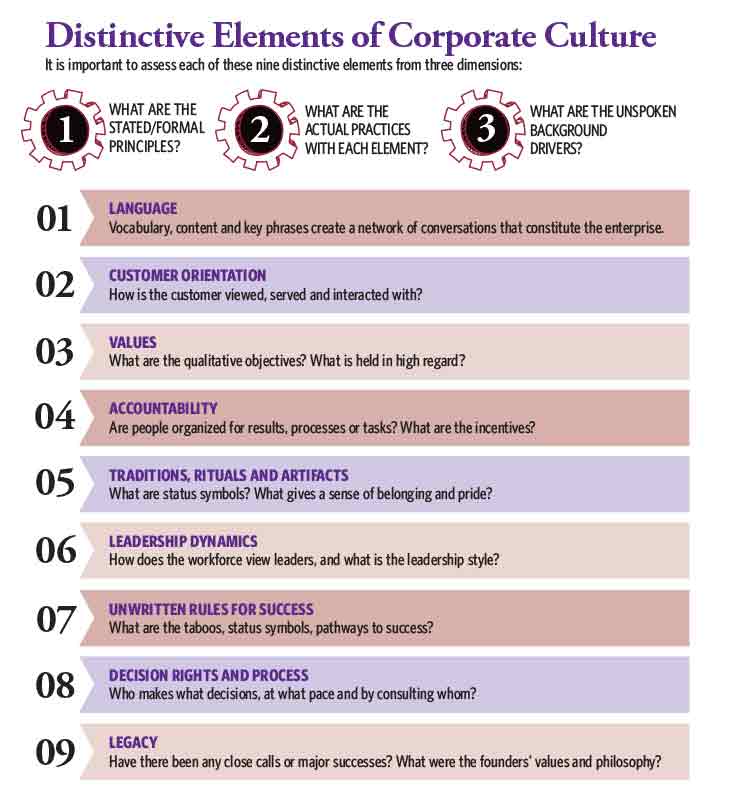

Companies that want to embed design thinking would do well to evaluate their current culture first. They should identify which of the company’s shared patterns of perception, thinking and acting may be at odds with design thinking and which ones are in harmony with design thinking’s key principles of empathizing, defining, ideating, prototyping and refining. The “Distinctive Elements of Corporate Culture” (see figure below) can be used as structure for making this critical assessment.

Said another way, design thinking cannot simply be wedged into an organization whose values are at odds with design thinking’s values. As Jeremy Utley, the director of executive education at Stanford’s d.school, a leader in design thinking, has said, “It’s a fool’s errand to try and go against the culture. You have to find the elements of your business culture that support [design thinking’s] kind of working and thinking mindset.”

If an organization is to embed design thinking, it must reveal, confront and take responsibility for all aspects of its current culture. Then it must design a culture that leverages design thinking for success in the marketplace of the future. (Not coincidentally, the application of design thinking can enable this step.) Finally, the firm must rapidly make the needed changes. Any other process risks simply dressing up the old culture without changing it. And that can result in the new culture unwittingly inheriting aspects of the old culture—aspects that undermine the advantages of design thinking.

WHAT IS CORPORATE CULTURE?

Every organization of any significant size—whether a commercial enterprise, a nonprofit charity or a governmental agency—operates within its own distinctive culture. Because it influences, shapes and distorts the actions, perceptions and thoughts of the people within the company, corporate culture is a singular determinant of an organization’s effectiveness Share on X and can be an arbiter, or at least a critical factor, in long-term success or failure.

Distinguishing Corporate Culture

Corporate culture is the particular condition in which people perceive, think, act, interact and work in a particular organization; it acts like a force field or an invisible hand. It shapes, distorts and reinforces the perceptions, thinking and actions of the people within the company, whether realized or not. Corporate culture is the unwritten rules for success inside the corporation, creating unseen walls and boundaries. It is the corporate paradigm. In short, it is whatever is reinforced within the organization. Analogously, it is like a company’s personality.

In many cases, that invisible hand offers a company a huge competitive advantage in markets, where the differences between competitors are limited. Southwest Airlines, long lauded for its unique culture and for being the most consistently profitable U.S. airline over the past three decades, is a good example. The company’s co-founder and former CEO, Herb Kelleher, once said that Southwest’s culture is the hardest thing for competitors to copy. Competitors “… can get all the hardware,” Mr. Kelleher said. “I mean, Boeing will sell them the [same] planes. But it’s the software, so to speak, that’s hard to imitate.”

It is important to note that Southwest’s culture is dynamic. It has kept up with the company’s incredible growth over the decades, helping keep Southwest near the top of the airline industry.

That is often not the case for established companies. Often, a corporate culture becomes fixed and unquestioned, the absolute view of reality, how things are (and ought to be), rather than simply a way to work—the right way rather than a way. In those cases, the organization loses flexibility, waste increases and execution slows.

Remember, we said that corporate culture is the unwritten rules for success inside the company. In healthy companies, the arbiter of behavior and success is the marketplace, and the corporate culture adapts to market forces.

When past ways of working culture take precedence over leading or responding to market change, success becomes pleasing the boss and fitting in.

Corporate culture is the particular condition in which people perceive, think, act, interact and work in a particular organization; it acts like a force field or an invisible hand.

In order to avoid this trap, organizations must empower and enable their people to continually invent new ways of competing and allow them to try to change the rules within the marketplace, as well as inside the corporation itself. This can happen either through a conscious and methodical cultural reinvention process or by building a spirit of renewal and reinvention into the culture itself.

Design thinking promises to do just this. It challenges existing assumptions about what customers want and need. It constantly pushes the organization to reconsider its marketplace offerings and how work gets done. And it asks people in the organization to work collaboratively to build something new.

CORPORATE FORCES THAT UNDERMINE DESIGN THINKING

In most enterprises—especially in large and successful enterprises—there are usually aspects of the culture that inhibit design thinking and innovation. These aspects show up in the practices, structures and systems of the organization, as well as in patterns of perception, thought and action. In their groundbreaking book The Power of Strategy Innovation, our Insigniam colleagues Bob Johnston and Doug Bate contemplated three forces that block innovation.2

More accurately, those can be seen as ways of perceiving, thinking and working—not actual forces—that can be neutralized through a designed corporate culture and attendant practices, systems and structures. But an analogy of forces is useful.

Corporate Gravity

Speaking analogously, corporate gravity is a hidden force that pulls your employees back to familiar ground—what is proven and known—rather than freely launching them toward innovation. The pull of the corporation is greater than the pull of the consumer and the marketplace. Corporate gravity is a product of the worldview and concomitant processes, systems and structures that protect the legacy business model and core products or services. Corporate gravity pulls resources to maintaining and improving what is perceived as the source of corporate success.

To achieve success, ultimately, any organizational transformation must be led by the chief executive. Having said that, an antidote for corporate gravity is to appoint a chief change officer or a chief innovation officer (CIO). This executive is seen as the hand and brain of the CEO, has a budget and a department under her or him, and has the accountability and commitment to embed design thinking in the corporate culture. This CIO has the power and authority to initiate, lead and manage change. For companies moving toward a design thinking model, the change can be facilitated by an executive who can bridge the gap between top management and the design and innovation teams—someone who can bring their two worlds closer together.

Corporate Immune System

Your body’s immune system rejects and fights foreign substances. It is an involuntary response. In an analogous way, organizations can seemingly reject and fight changes to their culture, even when the leaders are actively leading change.

There is no such thing as inherent resistance to change. People will not make changes if they are threatened by those changes. People will rapidly adapt to and/or cause change when they can see an opportunity for themselves.

There is no such thing as inherent resistance to change. People will not make changes if they are threatened by those changes. People will rapidly adapt to and/or cause change when they can see an opportunity for themselves.

All successful employees possess a key item of knowledge: how to make their managers happy. Do bosses demand that the current product development process be executed exactly as laid out in the corporate product development manual? Well then, how likely are employees to apply design thinking to that process, potentially disrupting it or completely reinventing it? How will they know how to make the bosses happy then?

This is one of leadership’s toughest challenges. Effective corporate change demands conversations—lots of them. Managers must tailor their message to individuals or, in a large-scale change process, tailor it division by division. What will inspire the scientists and engineers? What will move the marketers? Managers and executives need to interview and observe people in those divisions. They must then design a conversation that will open up opportunities for their people. In other words, executives and managers need to bring the designer’s tools and methods to their own work. That way, not only are employees engaged in the change, but they also see design thinking in action.

Corporate Myopia

There is a joke:

Question: How many designers does it take to change a light bulb?

The designer’s answer: Does it have to be a light bulb?

The power of design thinking is that it asks those engaged to think in different ways—about the product itself, the way the consumer will use it, the way it will be made. Everything is up for contemplation and a shift in perspective. That can be a problem for companies that are undergoing a transformation to design thinking while also operating an ongoing business.

Corporate myopia keeps executives from seeing value in innovations, including new methods like design thinking. Successful executives think that they know what the consumer wants and what will succeed in the marketplace. A breakthrough innovation in a product or a process may threaten an executive’s sense of his worth or not fit her understanding of what is valuable or not conform to the corporate strategy. In some companies, anything that does not hit financial hurdle rates or show well on forecast sales volume evaluations never makes it to market.

On several occasions, Nestlé executives tried to kill the now-successful Nespresso coffee system. Nestlé was in the food business, not the kitchen gadget business. Executives were skeptical of a technology developed by research and development (R&D) that did not fit the mass-market business model of the time and was a major departure from most of Nestlé’s lines of business. The Nespresso System survived and thrived when it was established as a separate company, in a different building, and an outsider was brought in for new perspectives and ideas.

The antidote to corporate myopia is design thinking itself. Share on X Rather than executives determining the value of an innovation, design thinking prototypes are held and actually used by consumers or users. Consumers and users determine value and how to improve or add value.

FOUR PILLARS OF INNOVATION FOR ENABLING DESIGN THINKING

No one, not even expert mountain climbers or the Sherpas who live in the Himalayas, just shows up one afternoon and starts climbing Mount Everest. The effort takes years of experience and months of preparation and requires that many things go to plan.

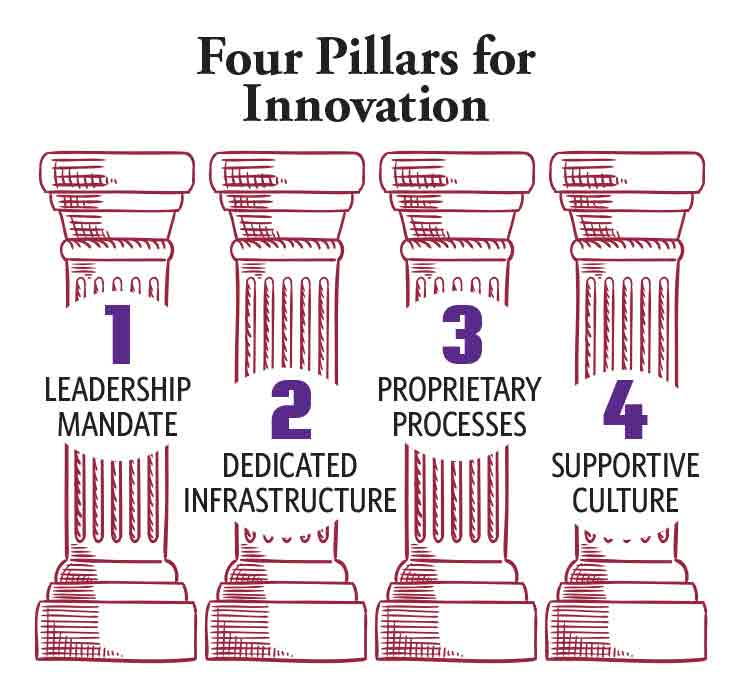

In the same way, design thinking cannot be embedded in a corporate culture without taking the time to build a stable base on which that change will rest. In The Power of Strategy Innovation, Mr. Johnston and Mr. Bate proposed that there are four critical pillars that support advanced strategy innovation. The idea is expanded and adapted to support effective design thinking. No one, not even expert mountain climbers or the Sherpas who live in the Himalayas, just shows up one afternoon and starts climbing Mount Everest. The effort takes years of experience and months of preparation and requires that many things go to plan.

Pillar 1: Leadership Mandate

The top executives have to commit to innovation using design thinking as a corporate priority; this is the corporate equivalent of Agamemnon hauling his ships onto the beach and burning them. The requirement for design thinking has to be baked into the corporate strategy. The executives have to learn and practice design thinking. They have to be committed to leading its adoption throughout the organization.

They have to design and communicate the case that innovation and design thinking are critical to the future of the organization. That mandate needs to be loud and clear and relevant to employees across the enterprise. They also must give clear permission to do fresh thinking and back this up with funding, people, time and space.

To illustrate: When A.G. Lafley, Procter & Gamble’s CEO, set out to remake that company around design thinking in 2001, he said, “We will not win on technology alone. Therefore, we need to build design thinking into the DNA of P&G.” And he backed those words up with his own actions.

Mr. Lafley was a regular attendee at workshops focused on design thinking, where designers were paired with senior managers so both could share the principles of design thinking. He also routinely received input from an external design board (those fathers of design thinking, among others), set up to critique P&G’s design decisions. He met regularly with the design executive whom he had tasked with overseeing the transformation, Claudia Kotchka, vice president for design, innovation and strategy, so that he could stay informed about the latest steps in the process. On virtually every business trip, he took time to go into consumers’ homes and observe how they lived. In those ways, Mr. Lafley communicated and led, in both words and actions, the vision and commitment to make P&G a company built around design thinking.

Pillar 2: Dedicated Infrastructure

A dedicated infrastructure organizes people, resources, budget, timelines, space and metrics. The dedicated infrastructure always mirrors the seriousness of the mandate. If there are visible resources invested in supporting the mandate, it is taken seriously. If not, it can be seen as lip service. It can include specific organizational roles, such as the office of innovation, a function that goes beyond new products or setting up self-managing teams.

To illustrate: A few years ago a large, successful health care enterprise held a typical executive offsite. The top executives discussed good news. Revenues were steadily increasing. So, too, were margins. They discussed a strategic plan that had been developed to ensure continued growth. But then came a surprise.

“We realized,” says one top executive, “that what had gotten us this far wasn’t going to get us where we wanted to be in the future. We took a real gut check and asked, ‘What do we need to change to achieve the strategic goals we had set?’ and ‘Are we going to make the investment in those changes?’”

The answers were eye opening. It was decided that the corporate culture needed to be redesigned with a focus on patients. The corporate culture had been centered on fiscal discipline, a heritage that was valued and honored.

Centering on patients would require a transformation. It was also decided that this transformation was worth the investment of money, time and the risk involved in changing the operational values of a financially stable enterprise because the executives were smart enough to realize that the risk of staying the same was even higher.

When an organization takes that kind of risk, though, it does not take it lightly. In this case, they executed systematically, step by step.

Step 1: Conduct a cultural assessment.

A cultural assessment of custom-designed questions was used for interviews and surveys of employees from every level, function and geography in the company to reveal the current culture. This process is not unlike the ethnographic tools that design thinking relies on to reveal the needs of consumers whom designers hope to help. The assessment was conducted against the “Distinctive Elements of Corporate Culture.” The analysis and report from the survey highlighted key aspects of the culture, the aspects that would support the strategy and those that would inhibit it, and recommendations to initiate the transformation.

Step 2: Set up an office of transformation and a transformation leadership team.

They called this team “the leadership coalition.” It was composed of 40 people from across all divisions of the organization. While not every team member was dedicated full time, they allocated a set amount of time for their new roles, as if part-time jobs. A full-time transformation executive was appointed and acted as team leader. The CEO’s opening statement on the coalition’s first day was that the group was to leave their titles at the door as they drafted a new vision, a new mission statement, new corporate values and new operating practices for the company.

Step 3: Set a budget and some deadlines.

Cultural transformation is neither quick nor cheap. It has hard costs and the need for sustained effort—a test of commitment, all of which should be considered carefully in advance. The company had an 18-month window for its first, most important phase of cultural transformation and allocated a specific dollar amount to make that change happen. The leadership coalition set a timeline working back from the close of the window.

Step 4: Create a team to win over the team.

An enrollment team that drew employees from all levels and functions of the organization was asked to inspire and engage the workforce to adopt the company’s new direction, even as it was being developed. These team members were trained in design thinking, effective communication and enrollment. They designed both the message and delivery methods to fit the company and its people.

“We took a real gut check and asked, ‘What do we need to change to achieve the strategic goals we had set?’ and ‘Are we going to make the investment in those changes?’”

Step 5: Create a big commitment, new capabilities and increased capacities, and lots of project teams.

This company also created a 30-person Keystone Project Team that, as its name suggests, was responsible for developing and executing a key project that would move the company to its new customer-focused goals. A keystone project is a multiyear commitment to producing critical results that can only be accomplished in the new culture. The Keystone Project Team commissioned project teams to move the keystone project forward and to deliver the intended results.

At the same time, 18 of the company’s top executives were engaged in a yearlong leadership development initiative that would give them the skills to work in an environment where collaboration was emphasized far more than it had been. As part of the leadership program, each executive designed and led a leadership project.

As one executive said, “We developed a real focus on teams. There was much less interest in executives saying, ‘How can I get this done?’ and more on, ‘How can we get this done?’”

Within the 18-month window, the initiative delivered notable change and produced remarkable results, moving the company from the middle of the pack to near the top of its industry in the three key metrics used to measure success.

Note: The first rule of management is that you tend to get what you reward; obviously, everyone knows that a reward structure is needed to support the transformation. However, the second rule of management is that you tend to get what you measure; not so obviously, as part of the infrastructure, you have to put in place a scoreboard to measure the value generated by design thinking. Otherwise, the value of design thinking is lost in the mix of overall business results.

From the time he joined Clorox in 2009, Wayne Delker successfully drove new product development as head of research and development and then as chief innovation officer for the entire company. Dr. Delker invented metrics to measure the value derived from innovation that helped sustain executive management’s investments in innovation, creating a virtuous cycle.

Pillar 3: Proprietary Process

For an enterprise’s creativity, innovation and design thinking process to complement its culture, infrastructure and mandate, it must be their process, meaning it must be proprietary. The process needs to reflect the unique business and assets of the company, as well as its corporate culture; ideally, the process should evolve over time.

Learning from leading-edge businesses and educational institutions can and will provide value, so why not just cut and paste their process into your organization? When an organization tries to wedge another entity’s process into its own business, the background and organizational context that allowed the process to be successful in the originating company is lost. The implementing company often finds that the off-the-rack solution does not integrate with the other elements of its enterprise. Simply put, company X’s process will not fit company Y’s infrastructure or culture—organizational context—because it was not designed to fit. Context trumps content; context is decisive.

Consider this statement made by Norio Ohga, the former chairman and CEO of Sony, a company that has effectively utilized design thinking. “At Sony,” he said, “we assume that all products of our competitors have basically the same technology, price, performance and features. Design is the only thing that differentiates one product from another in the marketplace.” Design, implement and utilize a proprietary creativity, innovation and design thinking process for your company.

Pillar 4: Supportive Culture

A supportive culture is friendly to new ideas, ranging from incremental to transformational, and not just those from the top down. The culture has to avoid breeding a fear of risk and failure. Risk management is healthy; risk avoidance is deadly. A supportive culture limits corporate gravity, inoculates against the enterprise immune system and fights corporate myopia, the three forces we discussed earlier in this chapter.

Compare the corporate cultures of Boeing and Airbus, a duopoly of commercial airplane builders, and you will find that the cultures are not even remotely similar, while their businesses are essentially the same. Think of the difference in corporate cultures at General Motors and Toyota.

This is why culture can be a huge advantage to some companies and a huge disadvantage to others. Remember the quote from Herb Kelleher at Southwest Airlines from earlier in this chapter about culture being a differentiator.

Cultures are not one-size-fits-all, and neither cultural transformation nor any serious design thinking endeavor can be a one-size-fits-all solution. These must be specifically designed with the existing culture and the corporation’s purposes and strategic intentions in mind. It must take into account the organization’s history, leadership and the mandate for change. Any plan put in motion to move an enterprise on an innovative path toward the future must first begin by recognizing and revealing where and what the organization is today—for better or worse.

FOUR STAGES OF TRANSFORMING TO A CULTURE OF DESIGN THINKING

OK, what if we have done a good job and convinced you that you need to transform your corporate culture with design thinking embedded in it? What if you have realized that a designed culture with design thinking embedded in it would give your enterprise a competitive advantage? Beyond the five steps and the four pillars outlined above, there are four stages to move your organization through for a successful cultural transformation (or any organizational transformation, for that matter).

Stage 1: Reveal

- What are the current aspects of your strategy, culture, processes and practices, systems and structures that enhance or inhibit design thinking?

- What are the hidden assumptions and deeply held beliefs that operate as an invisible force in the organization, telling people what is possible and not possible?

- What are the unwritten rules for success?

- How are new products and services brought to market? Is the company driven by internal decisions or customer insights?

- How do past failures, as well as successes, determine people’s thinking about the business, market dynamics, the competition and the customer?

- Are you innovating or just keeping up with the competition?

- Is your company’s relationship with the marketplace generative or reactive?

- Assess the current culture against the nine Elements of Corporate Culture.

Stage 2: Unhook

- What interpretations and beliefs cloud your view of the facts?

- To what degree do you blame forces outside of your control for your results, for example, “It is the economy,” “Marketing’s data is flawed,” “R&D cannot deliver on our customer needs?”

- Are you listening to what your customers are actually telling you, or do you already know what they are going to say?

- To what degree have your ways of doing things become the only way of doing things?

- What was said in the past and has now become the way it is?

- What are the sacred cows that need slaughtering?

- What assessments and judgments were made and are now related to as facts?

- Take responsibility for all of those conversations, stop relating to them as reality and put them aside.

Stage 3: Invent

- What will be the marketplace in the future?

- What kind of company would thrive and be wildly successful in that marketplace?

- What will be the purposes and ambitions of your organization that will inspire, challenge and excite the people who are your organization?

- What values will support your commitments? What are the fundamental principles that will inform people’s thinking and working?

- What is your leadership mandate for design thinking?

- What will be your proprietary innovation and design thinking process?

- How do you need to design your strategies, processes and practices, systems, structures and teams to leverage design thinking?

- What rewards and recognitions will reinforce and support design thinking?

- How will you measure the value generated by design thinking?

Stage 4: Implement

- Is leadership aligned with the future that is being created?

- In what new conversations will you engage the people of your enterprise?

- How are you going to get people to work across functional lines?

- How are you going to get the customer present in virtually every conversation and in every day of work?

- What projects and initiatives will utilize design thinking?

- Do you have a communication strategy that is sufficient to support the culture change (communication increased by a factor of 10)?

- What education and training will make a difference in empowering and enabling what people within the company?

- Are people held accountable for behaving and acting consistent with the new culture?

CONCLUSION

The lesson? Design thinking is a powerful new approach to business. Design thinking would likely be a source of competitive advantage, if it were embedded in the corporate culture, as well as the company’s strategy, processes and practices, systems and structures. Those companies that have embedded design thinking have found that it produces great results for customers, employees and their organizations as a whole.

To embed design thinking means both a strategic and cultural transformation for most large corporations. But cultural transformation is complex, difficult and fraught with risk. To use design thinking to achieve competitive advantage, the corporate culture must at least align with and, ultimately, pull for design thinking. By installing certain structures and by working on specific elements of the culture, executives can achieve this level of performance for their businesses.

1) Martin, Roger. “Incorporating Design Thinking into Firms,” Rotman: The Magazine of the Rotman School of Management, Fall 2005, Toronto.

2) Johnston, Jr., Robert E. and Bate, J. Douglas. The Power of Strategy Innovation: A New Way of Linking Creativity and Strategic Planning to Discover Great Business Opportunities, 2003, American Management Association, New York.