Quick Hits

The Challenge: Foster organizational change that drives results from the individual level.

The Plan: Assess employees’ personalities in a comprehensive way that captures the complexity of people, viewing them not as “human doings,” but as “human beings.”

The Execution: Create a new kind of assessment that offers employees a roadmap for improved communication, teamwork and leadership.

The Result: A new psychometric tool that provides the self-knowledge needed to drive widespread organizational change.

Stewart Desson hates putting people in boxes. As the CEO of Lumina Learning, he’s made it his mission to help companies understand the full complexity and dynamism of human personalities. Desson has built his U.K.-based organization, which he founded in 2008, around two simple but powerful ideas.

First, personality types as we have come to know them—“introverts” and “extroverts”—don’t really exist. Most people shift their personality to suit the moment. Second, the ability to deliver results starts with an accurate understanding of yourself—and those you lead. Share on X

“Really successful leaders have self-awareness,” Desson says. “They can read other people, they can adapt their style and connect with other people, and they can value others and co-create results together. Those are people who get breakthrough performance.”

Using a handful of different proprietary psychometric assessment tools, Lumina helps companies around the world improve their teams’ performance by bringing diverse personalities together and building rapport. Clients have included Goldman Sachs, Adidas and Pfizer.

Any company that uses typing models to recruit or assess employees is stuck in the past, says Desson, who has master’s degrees in operational research as well as change skills and strategies. “It’s quite funny that so many people are attached to typing models in businesses when the scientific models say types don’t exist. People who use typing models, in my opinion, are dated and they’re not looking at the latest scientific evidence.”

While at British Airways, where he worked for 15 years, Desson specialized in applying the scientific method to the company’s organizational change initiatives. He objected to being typed and labeled. “At British Airways, I was an extroverted intuitive—an ideas person. That is a really unhelpful label because it limits me. I might have lots of good ideas, but I’m capable of re-creating myself and building other skills, such as plan execution, as well.”

Insigniam Quarterly sat down with Desson to discuss how Lumina’s novel approach to psychometric testing embraces complexity of people—and by doing so, helps them drive remarkable results.

Insigniam Quarterly: What are the differences between traditional approaches to assessing personalities and Lumina’s?

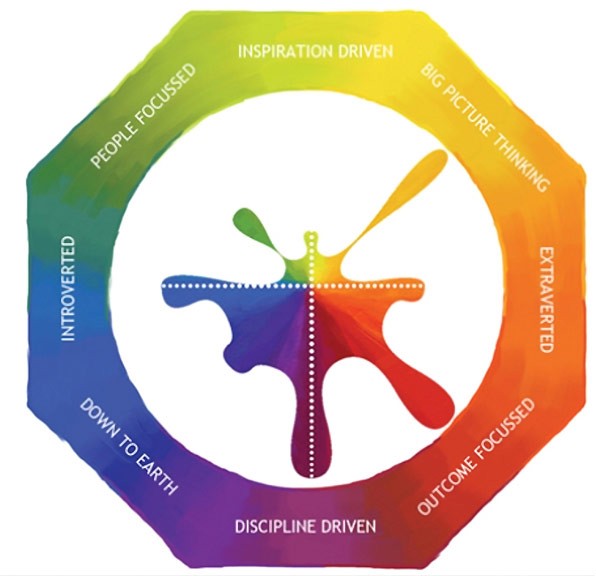

Stewart Desson: There are two big theories in psychology: typing and traits. Through my own research and that of a lot of other people, I’ve concluded very clearly that types actually do not exist. Most of us are a bit introverted and a bit extroverted. A data-based approach to introversion and extroversion suggests the scale is normally distributed and people are not types.

“Really successful leaders have self-awareness. They can read other people, they can adapt their style and connect with other people, and they can value others and co-create results together. Those are people who get breakthrough performance.”

We’ve brought in the idea that you can be opposites; you don’t have to be one or the other. We’ve also brought in the idea that we re-create our personalities in the moment in every new conversation. People shift on an everyday basis. Our assessments allow for that and allow people to be different in different contexts. We look at the dynamic of personality.

I’m really on a passionate mission to say, “Let’s not label people, let’s not limit people, let’s look at them as who they really are. Let’s encourage people to be the contradictions that they are and have these different, opposite qualities in them.” I can be quite critical and logical, but I can also be quite compassionate. That creates some inner tension in me. It’s not always easy, but that’s part of my leadership style, and that’s what makes me who I am. Let’s measure and embrace that complexity.

IQ: So how exactly do you measure someone’s different personas within the work environment?

SD: In our model we measure the ones that are the most obvious, helpful and meaningful. There are three: the “underlying persona”—what are you like at your most comfortable? Then there’s the “everyday persona”—how you tend to behave when responding to your environment. And then the “overextended persona”—when you might be under pressure or overplaying your strengths.

Other questionnaires tend to measure one thing, like just your everyday persona, and then try to infer the other things. For example, a questionnaire might find your everyday personality to be quite direct, clear, candid and straight-talking. Then they’ll make the assumption that under pressure you could be a bit blunt, even a bit aggressive. But we found in our Lumina Spark assessment that this might not be true. You may be tough and so on when things are going well, but under pressure you might strive really hard to be nice and agreeable, try to pull everybody together to be in consensus.

IQ: How can the results of these assessments be used?

SD: The starting point is self-awareness. We help people find out who they are, understand if they’re more direct and forthright with others, or diplomatic and nice. The next step is using that knowledge to understand other people. Can I read them? Can I notice their emotions?

The third stage is building rapport, “speed-reading” people to notice their qualities. Most of us are not good, normally, at speed-reading. We’re good at doing our thing. We’re good at our job, our tasks, but we don’t always notice people’s different ways of being.

If we do those three things, the fourth thing we can do at work is co-create results with other people from a more collaborative space where we value different ways of being. At heart, that’s what Lumina is about, and that’s why personality is a useful thing to know about.

IQ: Can you give some specific applications?

SD: If I’m in a team, I need to understand my colleagues. For the team to be high-performing, I want to know how I can better connect with people. If I’m the project leader, I need to know how to value diversity in the team. I don’t want to just recruit people in my own image. I might want to recruit people who are quite opposite because the team is stronger with more diversity.

If I’m in sales and business development and I’m going to meet a potential customer, I need to build rapport quickly. That means I need to be an expert in reading them, connecting with them and communicating in a way that works for them.

IQ: How do you communicate the value of the assessment to companies?

SD: There are studies showing that when salespeople understand who they are and how to read their customers, they can increase sales by 25 percent over the next 12 months. That’s because they become a relationship master as well as a technical sales master.

With leaders, the typical metric that’s used is staff engagement. In order to have engaged staff, leaders need to do things like read their staff and treat them as individuals. They need to help them create meaning and purpose in their role, and they need to stimulate their intellect so they’re truly engaged in the role, rather than dominate them and tell them what to do. They need to find a way to empower their staff. All of that requires knowledge of who you are.

We want to see leaders who are more transformational, who engage their staff. We want to show quantified improvements through staff engagement surveys. There are studies showing that for every percentage point you put into staff engagement, it’s worth X million dollars depending on the type of business, its size, and so on.

The final area of trying to quantify improvement relates to high-performing teams. Can you quantify the comparative benefits and productivity of just a functioning team and a high-performing team? If you speak to a CEO and ask him or her what’s the difference between a functioning team and a high-performing team, they will give you an instinctive feel of what that could be worth to the bottom line.

“In my opinion, the best use of a psychometric is to catalyze a conversation to help people create meaning, figure out who they are, raise their awareness and change their behavior. That’s the perfect use.”

IQ: How are psychometrics misused by businesses?

SD: One of the biggest misuses is in recruitment—to screen out people who don’t match a particular personality type and just go for an oversimplified and particular sort of person. Anyone who does that is at risk of behaving unethically. You can get sued for doing that.

Another misuse is using psychometrics to box and label people. With modern computing power and algorithms, there is no need to oversimplify and type. But the worst use of a psychometric is to excuse behavior. I’ve had someone come to me and say, “I’m ever so sorry, Stewart. I’ve just really upset one of the customers. But you know what? I’m the extroverted thinker type, so I can be a bit rude and blunt. It’s just who I am.” That to me is a cardinal sin. We don’t find out about ourselves to excuse away our behavior. We find out who we are so we can adapt and change our behavior.

In my opinion, the best use of a psychometric is to catalyze a conversation to help people create meaning, figure out who they are, raise their awareness and change their behavior. That’s the perfect use.

IQ: How do you measure success?

SD: If we’ve rolled out assessments to a large group of people, we would expect to see the needle moving around staff engagement. If staff members are more aware of who they are and better connected, they should be more engaged.

We also expect the percentage of people who leave an organization each year will drop. One way of ensuring that organizations retain talent is to make sure their top talent is developed and given great opportunities.

If we are using psychometrics effectively in recruitment, that means that we are analyzing the jobs and correctly understanding what traits and qualities are needed. It means that when we recruit people, we’re assessing against some objective criteria that have been thought through. It means that in our interview, we are more likely to ask pertinent questions to find out about people’s true strengths and weaknesses. It means we’re more likely to recruit people who will perform better, and we’re more likely to recruit people who will stay in their job longer. We’ll have less of what we call PUREs—“previously undiscovered recruitment errors”—that emerge six months after someone joins.

Another measure is: Can we improve our retention rate, and can we improve the performance of new employees in their first 12 months?

IQ: Are there certain people poorly suited for these kinds of assessments?

SD: The biggest problem is when someone is worried what their boss might think, so they fill in the questionnaire thinking, “I need to please the boss.” Or they’re worried people will expose their weaknesses so they admit to none. These are challenges.

I think we need to acknowledge that whenever you get someone to fill in a questionnaire, you may be creating anxiety in that individual. The onus is on the consultant to create the right environment to minimize anxiety so the whole process will be genuinely useful.