Though he likes to refer to himself as a “reformed banker,” Dennis McCuistion, former CEO of Texas-based The American Bank, still finds himself regularly having professional conversations with financial industry executives. Like just the other day, when McCuistion, now director of the Institute for Excellence in Corporate Governance at the University of Texas at Dallas, was at a roundtable meeting with, as he puts it, “a whole mess of board directors” from banks located around the country. “So,” McCuistion recalls, “I say to them, ‘As directors, wouldn’t you all agree that you’re pretty much change agents? And wouldn’t you agree that you’re mainly there to encourage the management team to make a positive disruption in leadership, at least from time to time?’ Well, they all nod their heads and say, ‘Yes, sure, of course.’ So then I ask them, ‘So how come you all sit in the same chairs at your board meetings every month? Do you really value change, or do you just say you value it?’ ”

Too often, the answer to that question — whether from directors in the financial industry or other industries — is not what CEOs who believe in the power of disruptive leadership would like to hear. “Many boards,” McCuistion says, “especially those with entrenched membership, consider change abhorrent, unless — and this is a big unless — there is a problem with the company’s performance. That’s unfortunate. Because it’s often better to have change, even radical change, before you get into problems.”

That was certainly the case at one company where McCuistion was a board director. From 2003 to 2007, McCuistion, who has hosted his own PBS business talk show for the past 24 years, was a board member at Affiliated Computer Services. That company, founded in 1988, started out as a data processing firm with modest revenues. But by the time McCuistion joined the board it had $4 billion in annual revenue and had morphed into a business processing outsourcing company. Three years after he left his directorship, ACS had hit $6.5 billion in revenues and was acquired by Xerox in a blockbuster merger.

That was certainly the case at one company where McCuistion was a board director. From 2003 to 2007, McCuistion, who has hosted his own PBS business talk show for the past 24 years, was a board member at Affiliated Computer Services. That company, founded in 1988, started out as a data processing firm with modest revenues. But by the time McCuistion joined the board it had $4 billion in annual revenue and had morphed into a business processing outsourcing company. Three years after he left his directorship, ACS had hit $6.5 billion in revenues and was acquired by Xerox in a blockbuster merger.

“Virtually the entire strategy of that company was changed — successfully — four different times in a 22- year period from its founding to the time it was acquired by Xerox,” McCuistion says. Why? Not because financial results were poor. Far from it. ACS was highly profitable during each major shift in strategy. But management foresaw changes coming in the marketplace for information technology and data processing services and decided to get out ahead of those changes rather than, as McCuistion puts it, “waiting for the company to go in the dumper.”

MAKING THE CHANGE

Making the changes at ACS required, as it does with every company, the active participation of the board. So how did management get directors to go along with four corporate reinventions even when the bottom line was solid? For one thing, McCuistion says, ACS was able to assemble a board that understood the company and its marketplace.

“The biggest problem you have as a CEO, and I have been there a few times in my life, is that it is the loneliest position there is,” McCuistion says. “Who do you talk to? Often, when you talk to your management team, they just tell you what they think you want to hear. So, when you’re a CEO who is proposing change, you need the board to assist in a dialogue about what the changes need to be and to understand the upside of the strategy you’re proposing and the risks inherent in the strategy. Then the board can make an informed decision about whether to accept this kind of disruption to business as usual or not.”

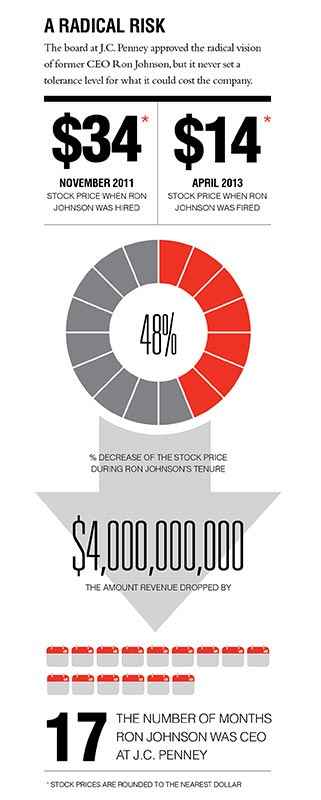

In a way, assembling a board of directors that gets your business may seem obvious. But it isn’t always done. Take the case of one major company in McCuistion’s backyard — Plano, Texas-based J.C. Penney. The retailer suffered a major meltdown under the disruptive leadership of former Apple executive Ron Johnson, who came into J.C. Penney seeking to do nothing less than reinvent the American department store. Instead, J.C. Penney saw its revenues cascade by $4 billion and its stock value fall by more than half before the board finally terminated Johnson just 18 months into his tenure. Of those 12 board members, just two had hands-on experience in the retail industry.

“Was there significant industry expertise on this board — people who would know something about what the retail business is?” McCuistion asks. “You need some people on a board who have ‘been there and done that,’ and I think that may have been where J.C. Penney’s board lost their way.”

TAKING THE RISK

Still, to the credit of J.C. Penney’s board, they were willing to OK a radical reinvention of a 100-year-old company. But how do directors, as McCuistion says, accept that they should “change seats” sometimes even when that means accepting the risk that comes along with disruptive leadership plans? McCuistion has a few thoughts on that.

1. ESTABLISH A CORPORATE “RISK APPETITE.”

“Risk appetite is a phrase that has only come into the corporate governance vernacular in the last five years,” McCuistion says. “It means the board has to decide how much risk it is willing to take to better compete. That helps the management team know what they’re likely to sell to the board when they propose a change.”

2. SET A TOLERANCE LEVEL FOR RISK.

At J.C. Penney, the board’s risk appetite was clearly large. But it doesn’t seem to have set a “tolerance level,” or specific parameters that would quantify that appetite for risk. “As a director, when change is proposed, you have to be able to say to the senior management, ‘OK, we’re willing to make this change, and here’s what we’re willing to let that change cost us,’ ” McCuistion says. “Maybe that’s a 10 percent decline in sales over six months or a specific loss of revenue or profit over a year. But it should be specific, because that lets management know what their performance benchmarks are. And if those aren’t hit, then management knows that either the board is going to pull back or they’re going to have to come back and re-sell the board on a new strategy.”

3. MEASURE THE CHANGE PERFORMANCE.

On ACS’s board, McCuistion was on the audit committee, which meant he had oversight of the company’s voracious appetite for mergers and acquisitions. ACS’ board had a specific tolerance level for the risk it was willing to take in those acquisitions and monitored them carefully for a year-long period before fully folding the acquired company into ACS. “Directors have to be able to regularly monitor what’s going on when you’re making big changes,” McCuistion says. In fact, McCuistion says that being able to see how changes are unfolding can sometimes give the board a bigger risk appetite. That was the case at ACS. “The more we were able to watch and see that these acquisitions were going well, the more confidence we had in management’s proposals,” McCuistion says.